The following important and timely article by UCC’s Dr Stephen Thornhill, appeared in the Irish Examiner Newspaper on 22nd October 2022, along with other articles which provide a difficult but critical information on the current food crisis in the Horn of Africa.

https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/spotlight/arid-40989254.html

Stephen Thornhill is director of the MSc in Food Security, Policy and Management and a lecturer in international development in the Food Business and Development Department, Cork University Business School, UCC.

Horn of Africa: The developed world must now show solidarity with those on the brink

The Horn of Africa is witnessing severe levels of food insecurity, with at least 36m now at the risk of starvation

SAT, 22 OCT, 2022 – 10:00

THE UN World Food Programme (WFP) and Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) recently estimated there are 345m people facing acute food insecurity around the world, with 222m people in need of urgent assistance in the worst-affected countries, and up to 50m on the edge of famine.

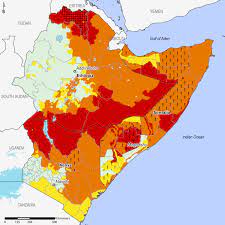

The Horn of Africa is once again witnessing some of the most severe levels of hunger, with at least 36m at risk of starvation across Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia. This has led to huge numbers displaced from their homes in search of food, with reports of many dying of hunger in transit.

The key causes include a fourth consecutive season of drought in the Horn of Africa, the worst for 40 years, which has wiped out livestock and crops. And there is a strong likelihood of below average rainfall over the coming months which would mean a recordbreaking five-season drought as climate change continues to disrupt weather patterns. High food prices are exacerbating the crisis throughout the region, whilst conflict continues to damage food availability and access in many countries.

In Somalia, famine is about to be declared unless urgent action is taken, with 300,000 people in the most extreme conditions of hunger (catastrophic) and 6.7m people facing emergency levels of acute food insecurity, representing over 40% of the population. The likelihood of below average rainfall in October to December will amplify the lower than normal harvests and high livestock deaths of the past year, leading to famine conditions extending across the country.

In Kenya, the drought has left many districts without any rainfall for three years, with over a third of the population suffering acute malnutrition.

In southern and eastern Ethiopia, the most severe drought in recent history has led to some 7m people suffering acute food insecurity. The Deyr rains up to January 2023 in Ethiopia are also forecast to be below average, as are those for eastern and northern Kenya.

Conflict is another major cause of hunger and starvation. In northern Ethiopia, and particularly Tigray Region, humanitarian aid continues to be prevented from reaching the population by the Federal government in an ongoing conflict with the Region of Tigray. This is in contradiction of UN Security Council Resolution 2417 on the use of starvation as a method of warfare.

In July 2022, it was estimated that 13m people were in need of food assistance in northern Ethiopia, and more recently, 5.4m in Tigray where 89% of the population was classified as food insecure.

Relief operations in Tigray have reached some 4m people since the start of August, but many households have only received limited and partial food baskets and the west of the province has remained inaccessible. Since the resumption of fighting at the end of August, there has been virtually no access and no humanitarian support going into Tigray. Ongoing conflict also continues to hinder access to food in parts of Somalia.

In Somalia, which imports 90% of its cereal needs, maize and sorghum prices are more than double those of last year, and food prices have now surpassed the 2011 famine levels.

In Ethiopia, food inflation was running at 40% higher in the first half of 2022, with maize prices more than doubling in the South.

Of the requested $3.4bn drought response needs for Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, only $1.9bn had been funded by the end of August, and it is anticipated that funding needs will increase in the light of recent assessments.

Given the huge impact of higher prices on food access for poor people and aid agencies, there also needs to be greater transparency around price movements on global commodity exchanges and other food markets.

Global cereal stocks have remained close to 30% of total needs since 2014, well above the average of some 20% in the previous decade.

Yet, despite the ample stocks and supplies, international cereal prices have risen sharply in volatile markets over recent months. Whilst the Russian invasion of Ukraine contributed to this, the fundamental market situation suggests prices should not have risen so sharply and may still be overstated, adding to the increased number of hungry people around the world.

Measures to improve market transparency and prevent excessive speculation and price volatility, need to be addressed by governments to ensure that everyone has access to affordable food.

A transition away from livestock production in the developed world to curb emissions would also help dampen prices of grain and other crops over time as more land becomes available for food rather than feed crops.

More pressingly, increased humanitarian aid and improved market management measures are vital to address the growing hunger crisis in the Horn of Africa and prevent famine.

The scale of such aid pales in comparison to the cost of capping energy prices by developed nations, who are ultimately responsible for much of the climate change induced hunger in the region.

The developed world needs to show global solidarity with the millions of people in the Horn of Africa struggling to survive in the face of multiple crises.