Contents (go to): Introduction ¦ Background ¦ Theories ¦ Action ¦ Process ¦ Articles ¦ Reflections ¦ Bibliography

Introduction

This website is the final product of our course work done at University College Cork for a University Wide Module titled, Global Citizenship and Development, UW0012, run by course lecturer Gertrude Cotter. The website serves as an addition to the Praxis Project.

The objective of our project is to highlight the importance of Women’s Empowerment. We have worked in collaboration with Trócaire. The two main components of our project consist of this website that documents each group member’s research and findings and a social media campaign to create awareness on the issues we have each investigated in relation to women’s empowerment.

Here are the members of our team:

- Eibhlis Brosnan: 4th year Commerce International with Hispanic Studies.

- Abigail DeTore: 3rd year Anthropology major, visiting student.

- Ruxue Mei:1st Year Master of Science in Design and Development of Digital Business.

- Taragh O Sullivan: BA Joint Sociology and Study of Religions Graduate and current Higher Diploma in Social Policy student.

- Alicia Rochford: 2nd Year Arts International Joint Honours (European Studies and Spanish).

- Xuege Wang: International relations (Master).

The website consists of individual research projects compiled into one cohesive space. Members of the team each did background research and used theoretical frameworks to further analyse the issues we are bringing forward throughout the project. The following topics are areas of interest that we have included on the website: women’s political participation, economic benefits of gender equality, women’s empowerment through technology, historical overview of women’s rights and the social role of women in Ireland. Team members have also used the following theoretical frameworks to guide their research: post-colonial perspective on women’s rights, social learning theory in gender socialization, feminist theory, human rights framework for female empowerment and intersectionality. In addition to research and theoretical approaches organized on the website, part of our project includes an action item intended to engage individuals to raise awareness and support global community initiatives to empower women. Our action item that we decided upon is a social media campaign on Instagram. We each created posts that were tailored to the individual research that we conducted for the project. We decided upon a social media campaign because of its ability to reach all demographics and a wider audience beyond the classroom. A social media campaign also offered our team the ability to have a space to collaborate throughout the process of this project and present our research in a creative way.

See below the home page for our website.

What does Women’s Empowerment mean?

Women’s empowerment means something different for everyone. If you do a google search for a definition of women’s empowerment, you will not see a one certain definition of what it is, but various different ones from organisations such as the United Nations and Trócaire. The common understanding of women’s empowerment is the want and need to give women a voice in every society that they are in and to give them all the support and power they need to exceed in life.

Trócaire is one of the organisations to support and empower women across the world. Trócaire supports, promotes and works with women to gain empowerment. They do this because:

- Across the world, 1 in 3 women experience some sort of violence in their life.

- Women and girls experience discrimination in every part of their lives including school, society, politics and at work.

- Sexual harassment and the threat to violence is a reality that women and girls have to face every day of their lives (Trocaire.org, 2023).

Trócaire is there to support women and girls to have a voice and to be able to make informed decisions that affect their lives. Trócaire empowers women in every aspect of their lives within their homes, communities and beyond (Trócaire, 2023).

Trócaire’s women’s empowerment programmes are based on an approach that works in many ways. Trócaire supports women and girls at individual, local and societal level and bring about change in people’s homes and communities (Trócaire, 2023). Trócaire do this by:

- Individual women: Trócaire builds confidence and self-esteem within women and girls by increasing knowledge and skills.

- Within households: Trócaire works towards shared decision making within the household in all communities that they work in.

- Within communities: Trócaire builds positive attitudes for gender equality. Trócaire does this by challenging negative attitudes towards gender.

- Wider society and institutions: Trócaire addresses power imbalances across the world. They do this by challenging political and economic structures in different communities and influencing different laws and policies (Trócaire, 2023).

Background research

Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation is also known as FGM, female circumcision or cutting (hse.ie, n.d). Female genital mutilation has no health benefits whatsoever. The practice harms women and girls and leaves them with lifelong health problems. Female genital mutilation is the part or while removal of outside female genitals. It is also the change in female genital organs for non-medical reasons (hse.ie, n.d.).

There are 4 major types:

- Type 1: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and/or the clitoral hood (World Health Organization, n.d.).

- Type 2: This is the part or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (World Health Organization, n.d.).

- Type 3: This is also known as infibulation. This type is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal (World Health Organization, n.d.).

- Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to female genitals for non-medical purposes, e.g., pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area (World Health Organization, n.d.).

This practice is a human rights violation of women and girls internationally. While there is almost 6,000 women living in Ireland having received FGM before moving here, the Criminal Justice (Female Genital Mutilation) Act 2012 makes it a criminal offence in Ireland to remove a girl from the state to mutilate her genitals (hse.ie, n.d.). While FGM is illegal in Ireland, known to happen around the world in 31 countries, most of which is in Africa. FGM is not a traditional practice in Ireland. People or women living in Ireland who have received FGM are mainly from Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Somalia (hse.ie, n.d.).

While FGM is happening in 31 countries, Somalia will be the focus country here. Somalia is one of the world’s countries. It is also an extremely unstable and complex nation, that laced an efficient government from 1991 to 2012. There was a great deal of violence and anarchy over those 20 years, and practically all the social, political, and economic institutions collapsed. Although there is optimism that Somalia will become more peaceful under the new administration, there are still significant obstacles to overcome (Trócaire, 2023).

In Gedo, Southern Somalia, Trócaire runs the only network of clinics and hospitals. Trócaire’s 24 medical institutions service 19,000 patients a month on average, with four primary hospitals. These facilities offer expectant women a safe environment to give birth in addition to providing essential healthcare for those suffering from disease and malnutrition (Trócaire, 2023). Due to limited medical facilities, inconsistent food supplies, and poor sanitation, people in Somalia are susceptible to sickness and illness. Pregnant women in Somalia face significant risks due to cultural traditions including female genital mutilation (FGM) and inexperienced home births of babies. (Trócaire, 2023). In Somalia, 95 percent of girls aged between 4 and 11 will undergo Female Genital Mutilation. FGM is seen as a rite of passage and an obligation and once the practice is completed, girls are considered women and are expected to be married off. FGM is a form of Gender Based Violence (GBV). FGM violates these girls and women’s sexual and reproductive health rights and their right to privacy and dignity (Trócaire, 2016).

Although FGM has been unconstitutional in Somalia since 2012, no legislation has been established to outlaw it completely, and until recently, public discourse on the topic was mostly frowned upon. The nation’s minister of religious affairs, Abdulkahdir Sheikh Ali Baghdad, has voiced notable support for ending FGM, stating that it is a custom that has no place in contemporary society. (Trócaire, 2016). FGM is a humanitarian crisis that needs to be stopped. Trócaire provides education to everyone to stop this and provides healthcare to women and girls who have gone through this trauma.

The Origins of Trócaire

Trócaire was established in 1973 by the Bishops of Ireland in response to poverty and injustice in the developing world. Trócaire, which translated means “compassion” in the Irish language, is its inspiration from scripture and the social teaching of the Catholic Church. The agency strives to achieve human development and social justice in line with gospel values. Trócaire was given a dual mandate: to support long-term development projects overseas and to provide relief during emergencies; and at home to inform the Irish public about the root causes of poverty and injustice and mobilise the public to bring about global change (Trócaire, 2024). Trócaire is also a member of Caritas Internationalis, a confederation of over 160 Catholic organisations that work in the areas of social justice and development, with its headquarters in Rome (Caritas Internationalis, 2024).

Trócaire works in three main areas: long-term development, by pairing with local partners to work on projects such as sustainable agrifood systems, female empowerment, peacebuilding, and rural entrepreneurship; short-term development, such as responding to emergencies with essential items such as food and medicine; and work in Ireland, where it is involved in campaigning for change and raising awareness of contemporaneous development issues (Trócaire, 2024).

Trócaire has worked in regions and states across the world. It carries out projects in Africa in the countries of Sierra Leone (as further discussed below), Rwanda, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Ethiopia, Sudan and South Sudan; in Central America in Guatemala and Honduras; in Myanmar in Asia; and in the Middle East in Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. Additionally, Trócaire provides funding for humanitarian aid in Yemen, Iraq, Eritrea, and the Philippines (Trócaire, 2024).

In Malawi, Trócaire works in areas such as diversifying agriculture production, establishing Village Savings and Loans Associations, building irrigation systems and encouraging alternative energy sources. It also works in the area of women’s empowerment, the topic of our project, in a number of ways: by exploring unequal power relations within communities, encouraging women;s participation in decision making, providing legal support to survivors of violence, stimulating the economic empowerment of women, and advocacy on issues such as gender-based violence and HIV (Trócaire, 2024).

Trócaire is funded primarily by Irish Aid, the EU and UK Aid; In 2022/23, €60.5m of Trócaire’s income came from governments and other institutional donors. Other funding partners include the World Food Programme, UNICEF, the World Bank and the FAO (Trócaire, 2024). The public is also a significant contributor to Trócaire’s operations: the financial year 2022/23 saw the public donate €33m to Trócaire (Trócaire, 2024).

Empowerment and Technology

In the digital age, technology has emerged as a cornerstone of empowerment, playing a pivotal role in bridging gender gaps and fostering equality. The intersection of empowerment and technology reveals a landscape where digital tools and platforms become instrumental in advancing the rights and opportunities of women worldwide. From social media channels that amplify women’s voices to e-learning platforms offering accessible education, technology serves as both a medium and a catalyst for gender equality (Anitha & Sundharavadivel, 2012).

Educational resources available online have democratized access to knowledge, allowing women in even the most remote areas to acquire skills and education that were previously out of reach. This accessibility is not just about learning; it’s about creating pathways to economic independence and career opportunities. Moreover, social media has provided a powerful podium for women to share their stories, advocate for their rights, and build supportive communities that transcend geographical boundaries (Oguns, 2023).

In addition to personal empowerment, technology facilitates women’s participation in the political sphere, enabling them to engage with and influence policy-making processes. For example, in India, mobile technology has enabled rural women to access market information, enhancing their agricultural businesses and fostering economic independence. Mobile technology, in particular, has been a game-changer for women’s economic empowerment, with mobile banking and financial services opening up new avenues for entrepreneurship and financial independence (Khera, P., Ogawa, S., Sahay, R., & Vasisht, M., 2022). This transformation is critical, as “The Digital Gender Gap” report in December 2022 highlights the increasing role digital tools play in providing economic opportunities to women globally. A notable case is the “SheMeansBusiness” initiative by Facebook, which has provided digital skills training to over a million women across multiple countries, significantly contributing to their ability to start and grow businesses online. This effort illustrates the profound impact of digital platforms in empowering women economically and politically worldwide.

The potential of technology to empower women is not without its challenges, encompassing a spectrum of issues that hinder the full realization of its benefits. Foremost among these are the digital divides that leave many women without access to essential technology, compounded by prevailing gender biases in the design and development of technology, as well as the pervasive issue of online harassment. Addressing these obstacles requires a multifaceted approach, including ensuring access to technology for women, providing education on its use, and fostering the development of technologies that are inclusive of gender diversity. This strategy aligns with the findings of the McKinsey Global Institute (2015), which underscored in “The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth” that fostering gender equality transcends moral and ethical imperatives, presenting a substantial opportunity to enhance global economic performance. In essence, the journey towards leveraging technology for the empowerment of all women is complex and fraught with barriers that necessitate proactive and comprehensive solutions.

As we continue to navigate the complexities of the digital era, it becomes clear that technology holds immense potential for driving gender equality forward. By harnessing this potential, we can create a world where technology is a universal tool for empowerment, breaking down barriers and paving the way for a more equitable and inclusive society.

Role of Women in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone is a country located in the west of Africa which has endured many civil wars and has a history associated with the slave trade. Specifically looking at the role of women in Sierra Leone today highlights the importance of the work ongoing in Sierra Leone that endeavours to promote and ensure the empowerment of women. Sierra Leone is considered to need a vast amount of intervention to improve the rights of women. Statistics show that “29.6% of women aged 20–24 years old who were married or in a union before age 18. The adolescent birth rate is 102 per 1,000 women aged 15-19 as of 2018, down from 139.4 per 1,000 in 2015.

As of February 2021, only 12.3% of seats in parliament were held by women. In 2018, 19.8% of women aged 15-49 years reported that they had been subject to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months. Moreover, women of reproductive age (15-49 years) often face barriers with respect to their sexual and reproductive health and rights: in 2019, 53% of women had their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods.” ((Country Fact Sheet | UN Women Data Hub, no date) After a recent talk with Yvonne Muto, who is the Global Women’s Empowerment Advisor for Trócaire, there was a peaked interest among the group about what exactly is considered the role of women in Sierra Leone. The issues that women in Sierra Leone face have caused such an invested movement of empowering women from so many NGOs, charity organisations and government institutions.

Some of these women empowerment actions that have been carried out by Trócaire in Sierra Leone include:

- “Building confidence, self-esteem, and awareness of rights.

- Developing literacy skills and leadership skills.

- Supporting women’s groups and women in leadership positions.

- Awareness-raising on gender roles and violence against women.

- Supporting survivors of violence with medical, psychological, and legal support.

- Challenging attitudes, beliefs, and unequal power relations, including engaging men and boys.

- Training and supporting authorities on their roles and responsibilities.

- Advocacy on preventing violence and promoting women’s participation in decision-making bodies” (Empowering women in Sierra Leone – Trócaire, 2022).

Women’s Political Participation

Women’s political participation is arguably essential in the progression of humanity. However, at the global level women are still chronically under-represented in political settings. Every nation is unique in its position towards empowering women to be involved in political/governmental leadership roles. According to UN Women, globally in executive positions of power, women comprise only 22.8 percent of cabinet members heading ministries that lead in policy areas and there are only 13 countries in which women hold 50 percent or more of those positions. At the current rate of progress, women will not see equality in national legislative bodies until 2063. Only three countries have 50 percent women occupying local deliberative bodies.

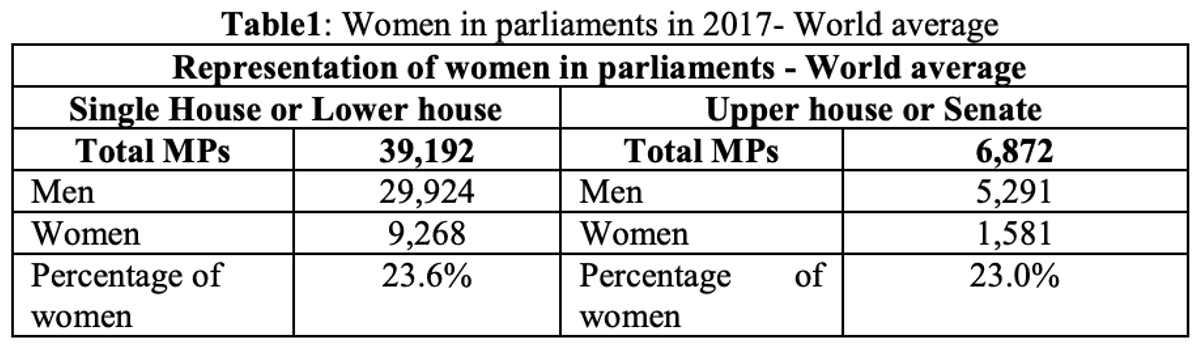

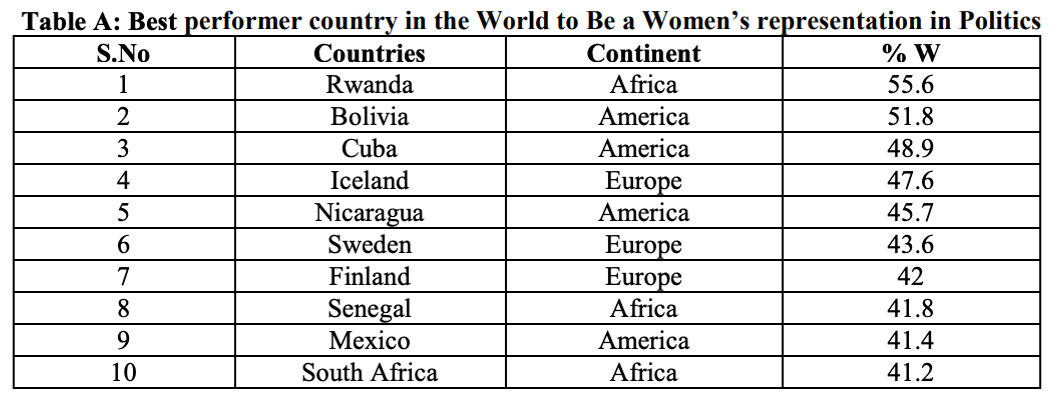

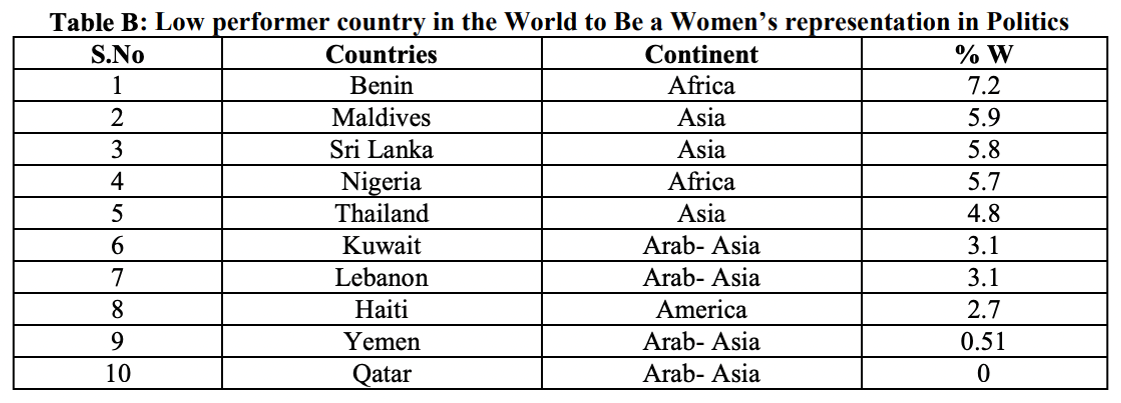

The following three tables come from an academic journal written by Dr Pankaj Kumar in 2017 titled Participation of Women in Politics: Worldwide experience.

Source: http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm (accessed: 11 Nov. 2017)

Women’s participation is women’s parliament can also be seen in Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua and Mexico, while in European countries Iceland and Finland, women’s representation is well-received. On the contrary, if we look at the countries, most of the Asian countries perform very low (see table B) in the parliament of women.

Table 1 above illustrates a clear uneven distribution of power globally of women’s leadership in parliament positions. The following two tables, table A and table B, illustrate the countries that have the most women in positions of political power and the countries that have the least women in positions of power. According to table B the majority of countries that severely lack women’s representation in parliament are countries in the Asian and Arab continents, with the number one country on the list being in Africa.

Given the data collected for this article, Dr Kumar concludes that women’s political empowerment comes only when women are properly represented in parliament because that is the space within which legal decisions are made. Various socio-economic factors in various countries around the world act as the barriers that keep women from occupying these positions of power. The research put into this topic, including the journal put forth by Dr Kumar leads one to question if the lack of global social and environmental progress is because half of the world’s population is suppressed.

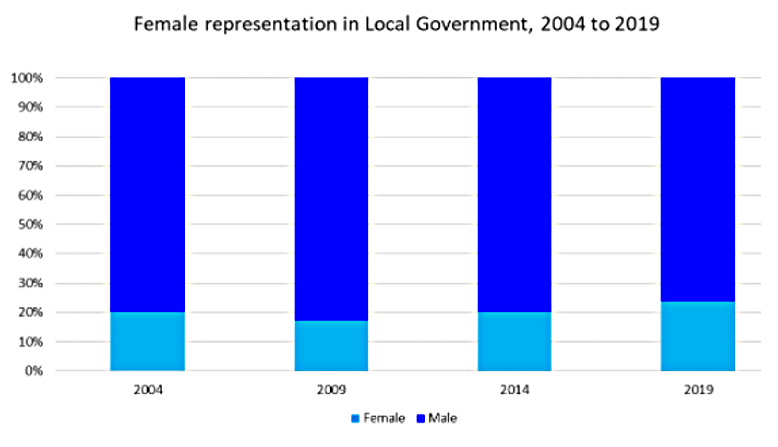

In Ireland specifically, according to Social Justice Ireland, between 2004 and 2019 women represented in local government institutions remained below or just slightly above 20%.

Social Justice Ireland recognizes access to affordable childcare as a barrier to women’s political participation and calls for the Irish government to create a cost-effective childcare network so that women are not forced to choose between their family and their career.

As of February 2023, Ireland ranks 98th in the world for women’s representation in government at 22.5% according to The National Women’s Council. The National Women’s council recognizes that representation is critical because marginalized groups of women are the ones who endure policy decisions in their fullest impact. Social change and the celebration and uplifting of diversity cannot occur when only one group of people is in charge of making political choices for the entire nation.

Post Colonialism

Our group recognizes that a critical component of women’s empowerment is using theoretical frameworks to more deeply understand the root causes and issues surrounding women’s disempowerment in order to bring about a more equitable future. An important framework that we think is necessary to highlight is the post-colonial framework and how it relates to women’s political rights and women’s political empowerment. According to Shehla Burney, author of Conceptual Frameworks in Postcolonial Theory, “Post colonial theory operates on the notion that imperialism and colonialism have affected the whole world, not simply the colonized nations” (Burney, 2012, 173-174). This journal written by Burney discusses how the post-colonial framework has been applied to several disciplines and has the potential to be used in education as a critique to curriculum and issues of representation that relate to race, class, gender, and diversity. Using a postcolonial framework is an important part of assessing the economic and political injustices that women face in specific areas around the world.

A journal published by Maria Martin de Almagro and Caitlin Ryan titled Subverting Economic Empowerment: Towards a postcolonial-feminist framework on gender (in) securities in post-war settings brings to light an important argument regarding looking at women’s empowerment through a postcolonial lens. The journal argues that systems currently in place that are meant to support women, are failing in this goal, specifically for women who live in post-war settings. This article particularly calls out the United Nations Women, Peace and Security agenda for reproducing a neoliberal understanding of women’s economic empowerment and thus their political empowerment. The WPS is designed to be the international site from which women’s political and economic empowerment is built upon, however Almagro and Ryan argue that “…the WPS agenda cannot materialize its transformative potential because of its piecemeal and partial approach to economic empowerment, characterized by a lack of engagement with (in)formal economies and a blindness to the complex relationship between the postcolonial state, violence and gendered processes of reconstruction” (Almagro and Ryan, 2019). These concerns carry strong merit.

In order to successfully empower women that are experiencing the detrimental effects of living within a post war setting, using a feminist postcolonial framework that deeply analyses structural power relations and representation in places of power is necessary in the empowerment process. The journal advocates for the use of a post-colonial feminist framework because this framework serves to reveal the connections between the Global North and Global South. Economic empowerment translates to political empowerment, when women have the means to support themselves, they can participate in the political process and garner legitimacy in the eyes of the law. The journal highlights WPS’s shortcoming in not acknowledging women’s formal and, specifically, informal participation in the economy. WPS efforts paint women who live in post-war settings as people in need of international assistance and it also takes on a gendered view of agency and employment.

Postcolonial feminism advocates against gendered experiences of men and women as it perpetuates women’s oppression, keeping them from occupying positions of power. Using a postcolonial lens is paramount in addressing women’s political participation in what are considered “third world” countries because it challenges dominant patriarchal norms and acknowledges that post-colonial conditions vary for women across various spaces, and this must be taken into account. Sara Hlupekile Longwe, supports the ideas put forward by Maria Martin de Almagro and Caitlin Ryan in Subverting Economic Empowerment, in her journal titled Towards Realistic Strategies for Women’s Political Empowerment in Africa. She argues that NGOs efforts to increase education for women and girls so that they become engaged in politics is a false correlation. She sites that the numbers do not suggest, specifically in Southern Africa that increased education leads to increased political participation. Longwe points to the “covert and discriminatory systems of male resistance to women who dare to challenge male domination of the present political system” (Longwe, 2000, 30) as the main barrier to women’s lack of political participation. Longwe’s journal points to the need for moral based interventions to challenge social norms, this call to action is like Trócaire’s call to change social norms repeatedly over time using the transformation household methodology.

Theoretical frameworks

Climate Change and Gender

Climate change is a global cause for concern. Not only does it have disastrous immediate effects such as the loss of biodiversity and the increase of sea levels, but it is also a “threat multiplier”, meaning that it escalates political, social and economic tensions. This element is particularly devastating for women and girls.

According to the UN Environment, 80% of the people displaced by climate change are women (Quiñones, 2021). Women are at risk in terms of natural disasters due to potential limited access to services and health care, particularly pregnant women. Vector-borne diseases such as malaria and Zika virus are also spread by natural catastrophes, which further complicate pregnancies (UN Women, 2022). In certain regions, many men are migrating from rural to urban areas to find employment, a trend spurred on by declining agricultural conditions. This results in women being left behind, responsible for the land and the family, but without the legal entitlement and social support to do so (United Nations Climate Change, 2022). Climate change also exacerbates violence against women and girls and makes them more vulnerable to human trafficking. Child, early and forced marriages also increase in climate-catastrophe areas, as they are often used as assets or to pay off debts due to losses incurred by disasters. Women are also at risk when they defend the environment: in Mexico and Central America between 2016 and 2019, about 1,698 acts of violence were recorded against women human rights defenders (United Nations Human Rights OHCRH, 2022).

Ecofeminism emerged in North American and European academic circles in the 1970s, linking the oppression of women and their bodies with humanity’s subjugation of nature. The key concept behind ecofeminism is identifying binary pairs, such as male and female and nature and civilisations. These binaries are known as oppositional dualism, and ultimately one binary is assigned more importance and power than the other by societies (Buckingham, 2015). Such binaries are used to justify patriarchal social structures and anthropocentric views that humanity is more valuable than nature. The framework has been criticised for insufficiently considering other factors, such as race and class, and has also been seen as an oversimplification of complex societal hierarchies (Bove, 2021). However, there are undeniable parallels and links between the climate crisis and the patriarchy.

Educating and empowering women can have a powerful effect on reducing a country’s emissions. By increasing access to family planning, women can decide how many children to have. This generally results in a decreased number of births, which reduces strain on ecosystems (Earth Day, 2020). By including women and girls in decision-making processes, a broader range of perspectives are represented, thus resulting in more equitable and innovative solutions. By outlawing child marriages and increasing access to education, girls and women can gain the skills and knowledge needed to combat global problems. Limited or non-existent access to digital training further disadvantages women: Sima Bahous, Executive Director of UN Women, has called the digital divide “the new face of gender inequality” (Dhar, et al., 2023). By empowering women smallholders, funding women’s organisations and supporting women’s health, women can be empowered in a way that benefits the environment, women, developing countries and the vulnerable of societies.

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory emerges as a critical lens for exploring and dismantling the structures perpetuating gender inequalities. Rooted in the pioneering work of scholars like Judith Butler, who scrutinized the societal construction of gender roles (Butler, 1990), and enriched by Kimberlé Crenshaw’s discourse on intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), it serves as both an academic discipline and a movement advocating transformative change towards gender equality. The origins of feminist theory trace back to the early movements for women’s rights, evolving through various waves to address a broad spectrum of issues. Initially focused on securing voting rights, the discourse expanded to encompass issues like sexual harassment and body shaming in the digital age, exemplified by the #MeToo movement (Zimmerman, 2017). Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality introduced during the Third Wave highlighted the interconnected nature of oppression faced by women from diverse backgrounds, thereby enriching feminist theory with a nuanced perspective on inequality.

At its core, feminist theory critiques the patriarchal system’s privileging of men over women. Intersectionality, a term popularized by Crenshaw, underscores the overlapping systems of oppression that individuals can face, challenging the monolithic view of female experience (Crenshaw, 1991). Furthermore, the assertion that “The Personal is Political” connects individual experiences with broader socio-political structures, emphasizing the societal underpinnings of personal situations.

Feminist theory encompasses various schools of thought, each advocating distinct strategies for achieving gender equality. While liberal feminism calls for equality through legal reforms, radical feminism seeks a deeper restructuring of society to dismantle patriarchy. Postmodern feminism, represented by figures such as Butler, questions the notion of a universal female experience, promoting a discourse that recognizes diverse identities (Butler, 1990).

The influence of feminist theory spans across disciplines, shaping literature, legal studies, and scientific research. In literature, feminist perspectives have challenged traditional narratives and advocated for women’s creative expression, as seen in the works of contemporary authors like Roxane Gay (Gay, 2014). Legally, feminist theory has informed significant advancements in addressing sexual harassment, guided by the scholarship of Catherine MacKinnon (MacKinnon, 2016). Furthermore, feminist critiques in science have unveiled gender biases in research methodologies, advocating for equitable practices (Harding, 2015).

Despite its achievements, feminist theory faces criticisms regarding essentialism and exclusivity, particularly its initial focus on the experiences of white, middle-class women. Contemporary feminist thought, responding to these critiques, emphasizes an inclusive and intersectional approach, striving for a balance between acknowledging oppression and championing empowerment (Collins & Bilge, 2016). This evolution underscores feminist theory’s dynamic nature and its ongoing effort to be more representative of all voices. In conclusion, feminist theory, with its comprehensive analysis of gender inequality and advocacy for social justice, continues to be a vital force in the pursuit of gender equality. Its commitment to embracing diversity and promoting empowerments for all individuals ensures that the struggle for equality remains inclusive and intersectional.

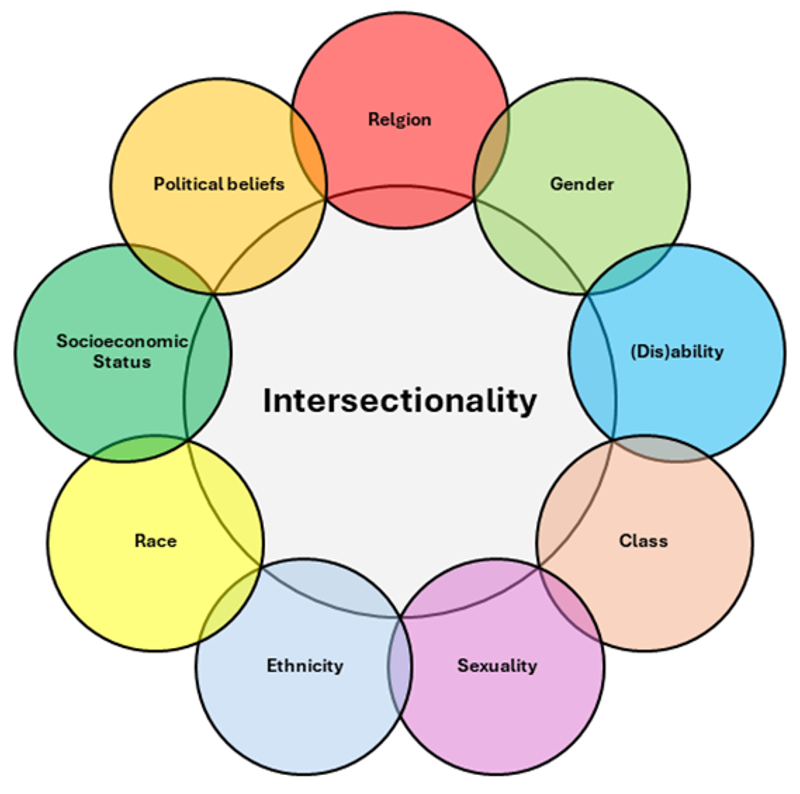

Intersectionality and Women’s Empowerment

Intersectionality is a core concept that should be considered when engaging with the topic of women’s empowerment. Intersectionality is the recognition of difference and the recognition that there is a multiplicity of difference. This difference often overlaps and is intersectional. The emergence of intersectionality is considered to have emerged from feminist theory and the writings of Black women. Intersectionality recognises that “All inequality is not created equal,”(Intersectional feminism: what it means and why it matters right now, 2020) while there is inequality facing women all over the world it is not the only inequality facing them. They might also be facing further social difference and inequality because of their race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, class, age and (dis)ability. “Intersectional feminism centres the voices of those experiencing overlapping, concurrent forms of oppression in order to understand the depths of the inequalities and the relationships among them in any given context” (Intersectional feminism: what it means and why it matters right now, 2020).

Understanding this theoretical framework is essential to understand and comprehend the need for women’s empowerment in today’s society. This oppression is still ongoing in varied stages all over the world. Referencing the recent talk with Yvonne Muto, who is the Global Women’s Empowerment Advisor for Trócaire, there is a substantial need to approach this oppression in different ways, depending on the region. In highly religious areas, they had to take a faith-based approach to even address the topic of gender-based violence. By taking this approach they are recognising that religion is a part of those in the community. While some would negate or belittle their religious beliefs, there must be a harmonious approach when talking about sensitive subjects such as gender-based violence. To encourage conversations and individual reflections surrounding gender-based violence, they engage with various respect and dignity-based religious teachings. Invoking new thoughts and much-needed discussions about gender-based oppression and oppression in general that surrounds them. This out-of-the-box thinking all relates to intersectionality, the realisation that women are not only their gender, class, sexuality etc. recognising that they do not need to belittle or bring down one part of their intersectional identity to empower the other. “Looking through an intersectional feminist lens, we see how different communities are battling various, interconnected issues, all at once. Standing in solidarity with one another, questioning power structures, and speaking out against the root causes of inequalities are critical actions for building a future that leaves no one behind”(Intersectional feminism: what it means and why it matters right now, 2020).

Action page

The action we decided to do for our group was create a social media account on Instagram to promote women’s empowerment. The username for the account is @womensempowerment2024. Each member of our group each had to make a post on what they believed to be women’s empowerment.

Alicia put up a question box asking the pages followers what they felt women’s empowerment was and also did a post on how we received a talk from Yvonne Muto who is a women’s empowerment adviser for Trócaire and spoke about the challenges facing women’s empowerment.

Taragh created the Instagram page and did a post on how Trócaire provides sanitary kits to the women of Zimbabwe who cannot afford to purchase these.

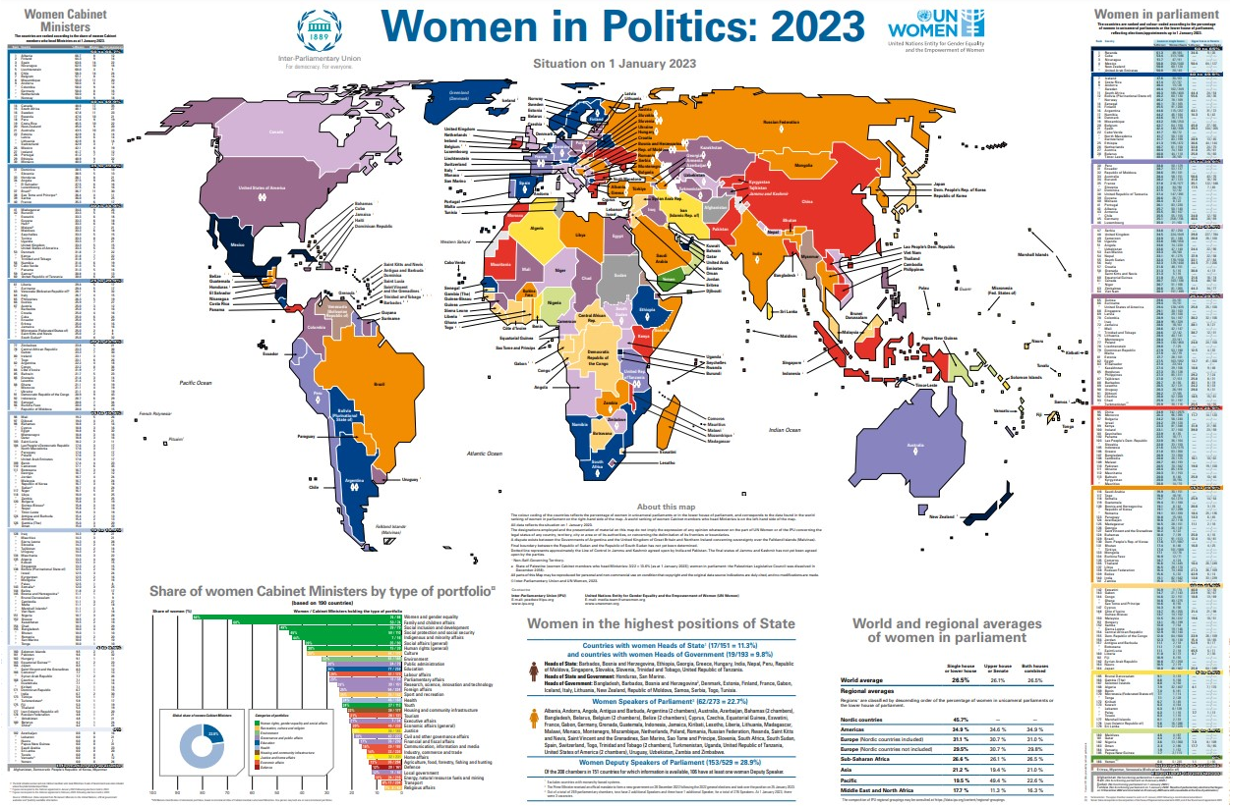

Abaigeal made two posts for the page. One post was an inspirational quote from Hilary Clinton saying ‘I have always believed that women are not victims. We are agents of change. We are drivers of progress; we are makers of peace – all we need is a fighting chance.’ Her second post was a recent map published by the United Nations women’s political participation. Eibhlis also made two posts on the page. One post was on how eco-feminism links the subjugation of women and the environment under the theme of patriarchal capitalism. Eibhlis other post was a quote from American poet, Maya Angelou saying, ‘Each time a woman stands up for herself, she stands up for all women.’

Process

Initial Process

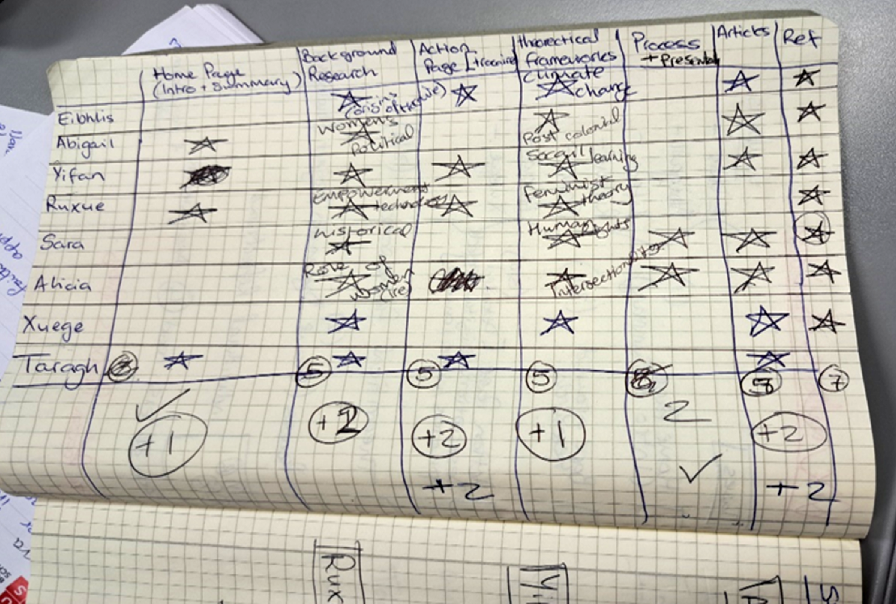

The initial planning of our project began when we reached out to each other to form a WhatsApp group. Within this WhatsApp group, we aimed to tackle the assignment at hand and broke down the necessary sub-contexts of our website. These subgroups consisted of

- Home page (which would feature a summary of our project and initiative, as well as introducing our eight members within the group).

- Background Research (which would include a wide range of topics that all contribute to or evolve the empowerment of women).

- Action Page (this page would include information on the actions taken by our group in the promotion of Women’s Empowerment).

- Theoretical Frameworks (This page would include information that revolves around the physical theories surrounding our background research and our group actions regarding women’s empowerment).

- Process (This page would outline the overall process of our project, outlining our roles within the group and highlighting the work taken in our final assessment for Assignment 5 which includes an overall presentation of our data to be presented for our website).

- Articles (Our article section was introduced to simply present how research and theory are present in everyday cases or scenarios. Each article is a real-life example of the theory and research presented earlier on the website. Providing case studies and real-life examples).

- Reflections (This section is where individual members of our project group, reflected on their participation in the project and highlighted the skills and insights they gained through their group work).

While our picture may look messy, when starting with multiple ideas and personalities the visual is never pretty or neat. When we met as a group before our night class, we divided out the work based on every group member’s strength and interest. Ensuring that the workload was evenly balanced and that everyone would understand their total workload.

Presentation Preparation

I was responsible for the preparation of the presentation, which took place near the end of the module. As the project progressed, many of our members had increasing workloads and were less able to find time to dedicate to the module. As a result, it became more difficult to schedule a meeting to discuss the presentation. Ultimately, we had a meeting with only half of the group. In that meeting, we analysed the presentation requirements. I divided the presentation into different sections, and I made a simple shared PowerPoint file and added everyone into the group. I wrote the headings of each section into the PowerPoint, and I then consulted my group members about their preferences. They offered to discuss their background research, and I volunteered to talk about my framework. I then counted the remaining sections, and I sent a message into our group chat which outlined the exact layout of the presentation. I then asked the members who did not have a role to present either the process, the action page or the article of interest. Everyone was eventually assigned a responsibility, and we set an agreed time and date to ensure that all of the correct work would be prepared in sufficient time. I requested everyone to include the relevant information within their part of the PowerPoint. I volunteered to do the introduction to the presentation, as I had been the one to organise its layout; I asked the member with the shortest section to do the conclusion.

Once everyone had completed their relevant section, I downloaded the PowerPoint to my laptop and modified it to make it more professional in appearance. I uploaded it to our group drive and sent it to our lecturer, to prevent any potential technical hitches. We practised our presentation together before we had the class. We noted that it was important that everyone introduce themselves and we discussed the importance of eye contact and body movement. I also observed that one group member’s part was significantly longer than the rest of the group, and she and I worked together to select the most important pieces of information and shorten her work. The presentation went excellently, and it was a great learning experience.

Articles of Interest – Referencing either the theoretical framework or Background research

Taragh’s Article

The article of interest that I have chosen is ‘Right to freedom from torture’: UN experts urge the Gambia not to decriminalise FGM. I found this article interesting because I thought it was interesting that a country seems to be going backward with Female Genital Mutilation and it brought be back to a few lectures from my undergraduate degree. In this article it was discussed how the law banning Female Genital Mutilation is trying to be repealed. The United Nations are urging the Gambian lawmakers not to repeal the law banning FGM as it would cause dangerous global precedent (Egbejule, 2024). FGM was banned in Gambia in 2015 in a second round of voting and it made the practice punishable by up to three years in prison or 50,000 dalasi’s (£586) in fines. This was the result of years of lobbying by human rights groups in Gambia and around the world, some led by FGM survivors (Egbejule, 2024). The new law was such a relief for women and girls in Gambia and it set a good example for other countries that practice FGM to follow. While it gave relief the women and girls, it was a unpopular decision in the most religious parts of Gambia (Egbejule, 2024). If the repeal of this law in Gambia happens, it ruins the work of Trócaire and would feel like it would be taking a step backwards after all the work they have done to promote female empowerment and the education they have given on the harms of Female Genital Mutilation.

Eibhlís’ Article

The article of interest I read was published by the World Bank: Nigeria to Scale Up Women’s Empowerment for Better Economic Outcomes (worldbank.org). I chose this article as it aligned with the theme of our project and my own degree, which is Commerce International.

The article discusses the World Bank’s approval of $500 million for the Nigeria for Women Program Scale Up in 2024. This financing aims to enable the government of Nigeria to improve the livelihoods of women. The programme endeavours to promote better education, health and nutrition; it aims to support communities and women to develop climate resilience; and it intends to address gender inequality (World Bank, 2023).

This project will support members of Women Affinity Groups (WAG). The fact that the initiative is focusing on specific groups will hopefully result in more tailored measures and more effective outcomes. The scale-up has three key areas: increasing emphasis on savings and leveraging existing income; making financial literacy a key element of institution building; and creating partnerships with financial service providers to improve female inclusion. The inclusion of women in these projects will support them in entrepreneurship and enable them to extract more value from their position in the value chain. These projects will also build climate resistance, as women will increase their earning potential and asset ownership (World Bank, 2023).

When more women join the labour force, economies grow, and economic diversification improves. Gender equality is associated with increased incomes per capita and more efficient and effective businesses. Female-led firms score higher on indicators that measure corporate, environmental and social governance; consequently, these firms tend to better manage natural resources (European Investment Bank, 2024). Another key element of women’s economic empowerment, the importance of which was insufficiently acknowledged in the World Bank article, is the recognition of the value of care work. Globally, women perform more than 75% of unpaid care and domestic work. By 2050, women will be spending almost 2.5 more hours per day on unpaid care work than men (UN Women, 2024). Another important trend in the labour market is that women experienced more damaging effects from the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, women made up 39% of the world’s workforce, but accounted for 54% of all job losses (Madgavkar, et al., 2020).

The World Bank article was interesting, as it detailed concrete, specific solutions to increase women’s participation in financial services. It also indicates the commitment of the World Bank to gender equality and transparency, and its emphasis on female entrepreneurship. However, it did not mention the issue of unpaid care work or the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on female employment.

Abigail’s Article

Women in Politics 2023: Women’s participation in politics is still far from equality.

This article published by UN Women uses the above graphic to illustrate the margins in equality between male and female participation in politics. It serves as an encompassing graphic and summarization of our group’s research into women’s political participation. The map was developed by UN Women and the Inter-Parliamentary Union and demonstrates that worldwide, more women are participating in political decision making yet gender equality is far from being achieved. In response to the data that the map displays, UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous, urges that there needs to be a paradigm shift that brings true equality to global political settings. The article shows that as of January 1st, 2023, 11.3% of countries have women Heads of State, that is 17/151 and 9.8% have women Heads of Government, that is 19/193.

While this is an increase from a decade ago, it still reflects poorly on global respect for women’s perspectives and the state of the world can arguably be highly improved if more women are given the opportunity to be in positions of power. Out of every global region, currently Europe has the highest number of countries led by women. Other regions should look to Europe as a guidepost, while Europe continues to make progress. Although still underrepresented, women hold positions mainly within environmental, public administration, and education sectors and positions on gender equality, human rights, and social rights while men continue to dominate the economic, defence, justice and interior sectors. Our group calls for women to continue occupying the areas that their participation is the most abundant in and begin occupying the same positions that are currently still dominated by men. A paradigm shift that includes women taking on roles within the defence and economic sectors of government could result in ground-breaking social, technological, and environmental progress for the global community.

According to this article, “Structural barriers to women’s equal participation in political life can only be addressed through temporary special measures with specific targets. One of the most important temporary special measures is gender quotas, which can be in different forms” (UN Women, 2023). The article goes on to discuss how during elections in Turkey, political parties can apply gender quotas for candidate lists and management/decision making positions.

Role of Women In Ireland: Referendum

Our research group is currently based in Ireland, and we felt it was best to also discuss the role of women in Ireland and the impending referendum which proposes changes to the Irish constitution that relates to Women and Family. The Vote on this referendum is due to be held on March 8th, 2024. “Éamon de Valera’s officials wrote the 1937 Constitution, with considerable input from the Catholic bishops, and it was narrowly endorsed in our first referendum in June of that year. Over its 87 years, the document has evolved through Supreme Court test-case rulings and 38 referendums” (Downing, 2024). With this referendum, the hope is to address the discontent with how women and families are referred to within the Irish constitution.

Our research group is currently based in Ireland, and we felt it was best to also discuss the role of women in Ireland and the impending referendum which proposes changes to the Irish constitution that relates to Women and Family. The Vote on this referendum is due to be held on March 8th, 2024. “Éamon de Valera’s officials wrote the 1937 Constitution, with considerable input from the Catholic bishops, and it was narrowly endorsed in our first referendum in June of that year. Over its 87 years, the document has evolved through Supreme Court test-case rulings and 38 referendums” (Downing, 2024). With this referendum, the hope is to address the discontent with how women and families are referred to within the Irish constitution.

Currently, the constitution reflects old and outdated ideas that do not reflect the Irish Republic of 2024’s views on women. The Irish constitution states, in Article 41.2: “ the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved” (Office of the Attorney General, no date). This reference that women belong or remain solely in the home has caused extreme and diverse reactions among the republic, with many not believing that in the present day, a statement like this referring to women remains in the constitution. This article is further proof that the empowerment of women globally never stops even in Westernised countries.

There is always room for progression and evolution of laws and constitutions. Women’s Empowerment must be a constant stream of ambition, enhancing self and state improvement together and all as one. While many would like to believe that the empowerment of women is at an all-time high in countries like Ireland, it does not mean that it stops here. There is still inequality for a lot of intersecting axes of women within Irish and Westernised society. This movement of empowerment will continue for all women in all aspects of society with integral work from women’s organisations and interest groups. Even through simple conversation, we can further empower the women around us to make a difference and continue the work of the courageous women who started this empowerment movement for women.

Xuege’s Article

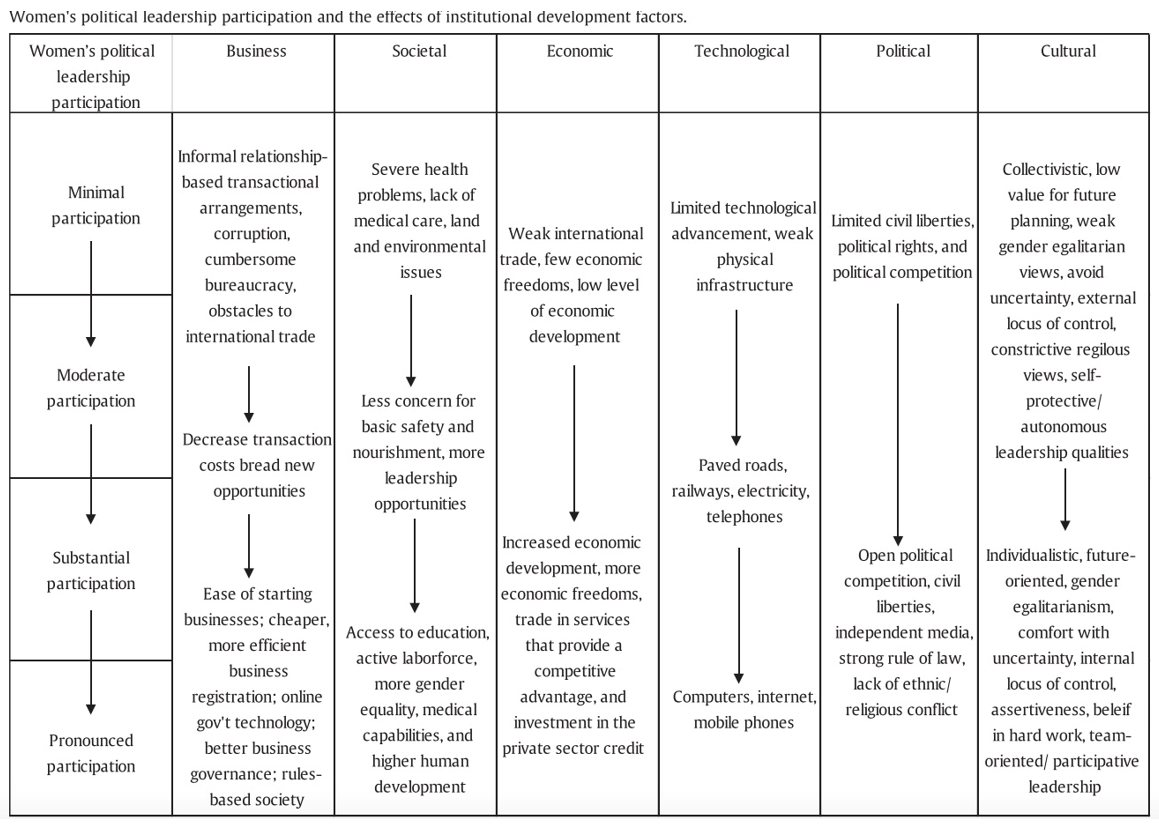

Women’s political leadership participation around the world

The various factors affecting women’s political participation vary around the world and continue to change with changes in national contexts. Our group is also conducting research in different directions. This article mainly considers the issue of women’s political participation through institutional analysis. What is the relationship between institutional forces at the social level and women’s participation in political leadership?

The article’s findings indicate that barriers to international trade, particularly those who report that customs and trade regulations are business practices. Companies are the main constraints to the practice, with an overall negative impact on women’s participation in political leadership. This may be because overall inefficiencies in government-corporate activity make politics less attractive to women, and perhaps to men as well. The article’s investigation also shows that political freedoms, namely independent media, open political competition, strong rule of law, respect for civil liberties, lack of racial and religious conflicts, freedom of assembly and demonstration, an effective legal system, individual rights in education and information sharing, and low levels of political corruption that provide opportunities for women to participate in politics. Governance provides an encouraging environment and opportunities.

Reflections

Eibhlis

It has been a fascinating process to learn about women’s empowerment and the many different forms it can take. It varies worldwide, and I have learned that gender is an important aspect of empowerment, but certainly not the only one; the significance of race and class in someone’s socioeconomic circumstances cannot be understated. I have learned more about women’s participation in politics and the ways in which greater participation can be achieved. The presentation from Yvonne Muto was excellent, as it provided an insight into the kind of work that Trócaire, an Irish NGO, does in the field of women’s empowerment. She discussed initiatives such as paradigm shifts, attitude adjustments, empowering women to take leadership roles, entrepreneurship, and upskilling. She also discussed dignity in crisis, and how Trócaire meets the needs of those suffering from crises.

I have also learned about ecofeminism. This is a theory that I had never heard of prior to this module, and it has been very insightful to discover the academic scholarship behind this movement. It was also interesting to reflect on prior theories that have been analysed and later criticised, as it shows the development and evolution of scholarship on this theme over time.

The group project element was certainly challenging. Not everyone in the group had the same form of communication, and on reflection, it would have been beneficial to establish boundaries and norms at the beginning of the project. There were also different attitudes towards the work, because for some group members, the module was optional, whereas for others it formed part of their final result.

I particularly enjoyed the outdoor class that we took as part of the Green Campus initiative. It was lovely to reconnect with nature and learn about the climate outdoors, as it made the issue of climate change seem more connected to our current reality. Additionally, it was refreshing to avoid looking at screens and sitting in chairs for two hours.

Abigail

This project and this class have both been integral parts of my academic experience at University College Cork as a visiting student this spring semester. The women’s empowerment project afforded me an opportunity to do research in areas that I am passionate about, work with fellow students from around the world and learn from an important human rights organization, Trócaire. I am very grateful to have had the experience to learn so much and meet so many new people while compiling what I have learned into an interactive, creative project that I can look back on in my future endeavours.

While there have been some hurdles that we as a group had to overcome throughout the process, when taking on a project with so many people of different academic schedules and commitments that is to be expected. Upon reflection of the entire process, I believe that we as a group could have done a better job at communicating and organizing times in which we could all gather to discuss the project. Individually, it is clear that we all struggled with time management, I personally believe that I could have done better spacing out the workload, however I was able to complete all my assignments on time, before the presentation date. I was also an active participant in the group chat and attended all but one of our group meetings. I would say the area we struggled the most on was committing enough time to the project individually and then communicating our progress to the rest of the group. We lost a member along the way and some people remained active in the group chat and attended meetings while others engaged very minimally.

My main area of focus was women’s empowerment in the political sphere. I completed three of my assignments around that theme. My assignments were to organize the home page, conduct background research, research a theoretical framework and find and summarize an article of interest for my chosen topic. Although I was not on the action committee, I suggested that the group take on a social media campaign given the time constraints that we encountered and that was the action that we ended up deciding upon. On the home page I summarized the intention of our project and put a space for every member to introduce themselves and added a visual. The following three assignments I looked into women’s political empowerment and researched using academic journals and UN databases/articles. I also contributed to the group’s social media campaign by sharing two posts regarding the theme that I focused my research on, women’s political empowerment, one post was a snapshot of one of my assignments and the other one is an inspirational quote.

Ruxue

Reflecting on our collective journey through the exploration of feminist theory, the pivotal role of technology in empowering women, and our concerted effort to amplify the voice of feminism through social media, it’s clear we stand at a unique confluence of theory and action. The foundational texts of Simone de Beauvoir, bell hooks, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, among others, have not only deepened our understanding of the complexities of gender inequality but also highlighted the transformative potential of technology in bridging these gaps.

Our discussions have brought to light the multifaceted challenges women face globally, ranging from the digital divide to systemic gender biases and the threat of online harassment. Yet, in every challenge, we’ve also seen opportunities for change, growth, and empowerment. The stories of women leveraging digital platforms for economic independence, the use of social media to form global networks of solidarity, and the emergence of e-learning as a tool for democratizing education exemplify the dynamic intersection of feminist theory and digital innovation.

Launching an Instagram account to spread feminist power is more than a project; it’s a testament to our belief in the power of collective action and digital engagement to effect change. This platform is not just a space for advocacy but a reflection of our commitment to embodying the principles of inclusivity, intersectionality, and empowerment in every post, story, and interaction.

As we move forward, it’s crucial to remain cognizant of the barriers that still exist and the ongoing work needed to dismantle them. Yet, this reflection fills us with hope and determination. The challenges are significant, but so is our resolve to contribute to a more equitable and just society through the tools and platforms at our disposal. This journey of blending theory with actionable steps on social media has reinforced the idea that every one of us has a role to play in the fight for gender equality. It’s a reminder that the path to empowerment is both collective and individual, carved out by our shared efforts and personal commitments to the cause.

Alicia

It has been an interesting journey with many ups and downs, but I am elated that we got there in the end. The topic itself interested me greatly from the start as many empowering women have inspired me throughout my life. I loved being able to implement some of my knowledge on intersectionality that I gained from one of my other courses into this project, I feel that this provided a great base of understanding when listening and reading numerous resource materials on this subject. The presentation given by Yvonne Muto was particularly inspiring as she explained her work and the strategies Trócaire used to combat GBV. She also explained the initiatives Trócaire aimed and implemented in certain areas to empower women in Africa. Her talk inspired me to further research the role of women in Sierra Leone (a place she mentioned) and to also post about her talk and discuss Trócaire’s strategy to combat GBV in my action post on our group’s Instagram page. This has been a long and arduous journey, completing this module along with all my main degree modules, extracurriculars and volunteer work, but it has all been worthwhile in the end. I feel that this project highlighted my time management skills and my talent for keeping on top of deadlines while working as part of a team. I feel I communicated well in our group’s WhatsApp group and helped others where I could. I feel that our meetings were generally productive despite the low turnout and that I efficiently communicated the minutes of the meetings to the other group members. In conclusion, I am happy that I took the initiative to sign up for this extra module and I feel that I have an enhanced understanding of the topic of Women’s Empowerment. I hope to apply my gained knowledge to future actions and assignments soon.

Xuege

This is a very strange journey, because I am personally very interested in the intersection of feminism and international relations. At the same time, the members of our group come from all over the world. Everyone has different ideas and views, which are strange and rich. improve my knowledge base.

Taragh

This was one of my favourite modules that I have taken in my time in UCC. Each topic every week and particularly my group’s projects, Women’s Empowerment, touched off areas of study in both my undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. My undergraduate degree was a Joint Degree in Sociology and Study of Religions and my Postgraduate degree is a Higher Diploma in Social Policy.

I thoroughly enjoyed doing the research for this project which will help me in my (hopefully) future career in Social Work. I enjoyed working with everyone in the group and I have learned how to work better in groups.

Bibliography

(2020). Intersectional feminism: what it means and why it matters right now [Online]. UN Women Headquarters. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/6/explainer-intersectional-feminism-what-it-means-and-why-it-matters (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

(2020). Intersectional feminism: what it means and why it matters right now [Online]. UN Women Headquarters. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/6/explainer-intersectional-feminism-what-it-means-and-why-it-matters (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

Anitha, L., & Sundharavadivel, D. (2012). Information and communication technology (ICT) and women empowerment. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 1(4), 143-152.

Bove, T., 2021. Ecofeminism: Where Gender and Climate Change Intersect. [Online]. Available at: https://earth.org/ecofeminism/. [Accessed 5 April 2024].

Buckingham, S., 2015. Ecofeminism. In: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). s.l.:s.n., pp. 845-850.

Bullough, A., Kroeck, K.G., Newburry, W., Kundu, S.K. and Lowe, K.B., 2012. Women’s political leadership participation around the world: An institutional analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), pp.398-411. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1048984311001573

Burney, S. (2012). CHAPTER SEVEN: Conceptual Frameworks in Postcolonial Theory: Applications for Educational Critique. Counterpoints, 417, 173–193. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42981704

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Caritas Internationalis, 2024. Who We Are. [Online]. Available at: https://www.caritas.org/who-we-are/.

Check out women’s empowerment work done by Trócaire (2023) Trócaire. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/our-work/womens-empowerment/ (Accessed: 13 April 2024).

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity.

Constitution Of Ireland [Online]. Radiological Protection Act 1991 (Ionising Radiati. Available at: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/cons/en/html (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

Country Fact Sheet [Online]. UN Women Data Hub. Available at: https://data.unwomen.org/country/sierra-leone (Accessed: 22 February 2024).

Crenshaw, K. (1991). “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Dhar, V., Chklovski, T. & Botti-Lodovico, Y., 2023. 5 reasons why empowering women and girls can revolutionise the fight against climate change. [Online]. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/05/5-reasons-empower-women-fight-against-climate-change/. [Accessed 6 April 2024].

Earth Day, 2020. WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT IS KEY TO REDUCING CLIMATE CHANGE. [Online]. Available at: https://www.earthday.org/womens-empowerment-is-key-to-reducing-climate-change/. [Accessed 5 April 2024].

Egbejule, E. (2024) ‘right to freedom from torture’: Un experts urge the Gambia not to decriminalise FGM, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2024/apr/11/right-to-freedom-from-torture-un-experts-urge-the-gambia-not-to-decriminalise-fgm (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Empowering women in Sierra Leone – Trócaire (2022).

European Investment Bank, 2024. Support for female entrepreneurs: Survey evidence for why it makes sense. [Online]. Available at: https://www.eib.org/en/publications/online/all/finance-female-entrepreneurs. [Accessed 18 April 2024].

Female genital mutilation (FGM) (no date) HSE.ie. Available at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/primarycare/socialinclusion/domestic-violence/female-genital-mutilation-fgm/. (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Female genital mutilation (no date) World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation. (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Female genital mutilation and pregnancy (no date) HSE.ie. Available at: https://www2.hse.ie/pregnancy-birth/support/female-genital-mutilation/. (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Female Representation in Politics in Ireland. (2022, June 8). Social Justice Ireland. https://www.socialjustice.ie/article/female-representation-politics-ireland#:~:text=20.2%20per%20cent%20of%20Local.

Gay, R. (2014). Bad Feminist: Essays. Harper Perennial.

Harding, S. (2015). Objectivity and Diversity: Another Logic of Scientific Research. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119836474.

J. Downing, (2024). March 8 referendums explained: What changes on women and family are proposed for the Constitution – and why? [Online]. Independent.ie. Available at: https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/politics/march-8-referendums-explained-what-changes-on-women-and-family-are-proposed-for-the-constitution-and-why/a404479153.html (Accessed: 21 February 2024).

Khera, P., Ogawa, S., Sahay, R., & Vasisht, M. (2022). The Digital Gender Gap, December 2022.

Kumar, Dr. P. (2017). Participation of Women in Politics: Worldwide experience. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22 (12).

MacKinnon, C. A. (2016). Butterfly Politics. Harvard University Press.

Madgavkar, A. et al., 2020. COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects. [Online] Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects. [Accessed 19 April 2024].

Martin de Almagro, M., & Ryan, C. (2019). Subverting economic empowerment: Towards a postcolonial-feminist framework on gender (in)securities in post-war settings. European Journal of International Relations, 25(4), 1059-1079. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119836474.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2015). The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth.

OGUNS, E. O. TECH-DRIVEN GENDER EQUALITY: EMPOWERING WOMEN IN THE DIGITAL AGE.

NWCI.ie, N. W. C. of I. |. (2023, February 27). 40% Gender Quotas Pave the Way for Full Representation of Women: NWC. National Women’s Council of Ireland | NWCI.ie’. https://www.nwci.ie/learn/article/40_gender_quotas_pave_the_way_for_full_representation_of_women_nwc.

Quiñones, L., 2021. Women bear the brunt of the climate crisis, COP26 highlights. [Online] Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1105322. [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Sara Hlupekile Longwe. (2000). Towards Realistic Strategies for Women’s Political Empowerment in Africa. Gender and Development, 8(3), 24–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4030459.

Social Justice Ireland. (2022a). Female Representation in Politics in Ireland. [online] Available at: https://www.socialjustice.ie/article/female-representation-politics-ireland#:~:text=20.2%20per%20cent%20of%20Local.

Somalia humanitarian support – our work (2023) Trócaire. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/countries/somalia/#ourwork. (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Trocaire (2016) Somali government pledges to pass legislation banning female genital mutilation, Trócaire. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/news/somali-government-pledges-to-pass-legislation-banning-female-genital-mutilation/. (Accessed: 25 April 2024).

Trocaire (2020) Seeking out stories of change in Sierra Leone – Trócaire. https://www.trocaire.org/news/seeking-out-stories-of-change-in-sierra-leone/.

Trócaire, 2024. About Us: History. [Online]. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/about/history/ [Accessed 9 April 2024].

Trócaire, 2024. Funders. [Online]. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/about/funders/. [Accessed 5 April 2024].

Trócaire, 2024. Our Work. [Online]. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/our-work/trocaire-supporting-peace-building-efforts-around-the-world/. [Accessed 3 April 2024].

Trócaire, 2024. Where We Work. [Online]. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/our-work/where-we-work/. [Accessed 19 March 2024].

Trócaire, 2024. Why We are Working in Malawi. [Online]. Available at: https://www.trocaire.org/countries/malawi/#ourwork. [Accessed 2 April 2024].

UN Women – Europe and Central Asia. (n.d.). Women in Politics 2023: Women’s participation in politics is still far from equality. [Online]. Available at: https://eca.unwomen.org/en/stories/news/2023/03/women-in-politics-2023-womens-participation-in-politics-is-still-far-from-equality.

UN WOMEN (2023). Women in politics: 2023. [Online]. UN Women – Headquarters. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/03/women-in-politics-map-2023.

UN Women, 2022. Explainer: How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected. [Online]. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2022/02/explainer-how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected. [Accessed 2 April 2024].

UN Women, 2024. Facts and figures: Economic empowerment. [Online]. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures#_edn23. [Accessed April 19 2024].

UN Women. (2023, September 18). Facts and Figures: Leadership and Political Participation. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures.

United Nations Climate Change, 2022. New Report: Why Climate Change Impacts Women Differently Than Men. [Online]. Available at: https://unfccc.int/news/new-report-why-climate-change-impacts-women-differently-than-men. [Accessed 4 April 2024].

United Nations Human Rights OHCRH, 2022. Climate change exacerbates violence against women and girls. [Online]. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2022/07/climate-change-exacerbates-violence-against-women-and-girls. [Accessed 5 April 2024].

World Bank, 2023. Nigeria to Scale Up Women’s Empowerment for Better Economic Outcomes. [Online]. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/06/22/nigeria-to-scale-up-womens-empowerment-for-better-economic-outcomes. [Accessed 18 April 2024].

Zimmerman, A. (2017). “#MeToo: The Hashtag that Sparked a Movement.” CNN. [Online]. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/30/health/metoo-legacy/index.html.

© 2024. All rights reserved. Praxis UCC.