Contents (go to): Introduction ¦ Background ¦ Theories ¦ Action ¦ Reflections ¦ Bibliography

Introduction

Zahra’s Part

Palestine Refugees

Who are Palestine Refugees?

Palestine refugees are defined as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”

UNRWA services are available to all those living in its area of operations who meet this definition, who are registered with the Agency and who need assistance. The descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children, are also eligible for registration. When the Agency began operations in 1950, it was responding to the needs of about 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, some 5.9 million Palestine refugees are eligible for UNRWA services.

Where do Palestine refugees live?

Nearly one-third of the registered Palestine refugees, more than 1.5 million individuals, live in 58 recognized Palestine refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

A Palestine refugee camp is defined as a plot of land placed at the disposal of UNRWA by the host government to accommodate Palestine refugees and set up facilities to

cater to their needs. Areas not designated as such and are not recognized as camps. However, UNRWA also maintains schools, health centres and distribution centres in areas outside the recognized camps where Palestine refugees are concentrated, such as Yarmouk, near Damascus.

The plots of land on which the recognized camps were set up are either state land or, in most cases, land leased by the host government from local landowners. This means that the refugees in camps do not ‘own’ the land on which their shelters were built, but have the right to ‘use’ the land for a residence.

Socioeconomic conditions in the camps are generally poor, with high population density, cramped living conditions and inadequate basic infrastructure such as roads and sewers.

Responsibility of UNRWA in camps

The responsibility of UNRWA in Palestine refugee camps is limited to providing services and administering its installations. The Agency does not own, administer or

police the camps, as this is the responsibility of the host authorities.

UNRWA has a camp services office in each camp, which the residents visit to update their records or to raise issues relating to Agency services with the Camp Services Officer (CSO). The CSO, in turn, refers refugee concerns and petitions to the UNRWA administration in the area in which the camp is located.

1967 Hostilities

In the aftermath of the hostilities of June 1967 and the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, ten camps were established to accommodate a new wave of displaced persons, both refugees and non-refugees.

Cities and towns

The remaining two thirds of registered Palestine refugees live in and around the cities and towns of the host countries, and in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, often in the environs of official camps. While most of UNRWA’s installations such as schools and health centres are located in the Palestine refugee camps, a number are outside; all of

the Agency’s services are available to all registered Palestine refugees, including those who do not live in the camps.

Source: https://www.unrwa.org/palestine-refugees

Psychological impact of the conflict on the well-being of Palestinians

Mental Health Challenges: The ongoing conflict has led to widespread mental health issues among children and young people in the Gaza Strip, including high rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. These conditions are heavily influenced by the constant exposure to violence and instability.

Research Gaps and Needs: Despite considerable research, there are still many unknowns about how war-related stress affects the mental health of young Palestinians. More studies are needed to better understand these impacts and to improve mental health services.

Scoping Review Insights: Recent reviews have shed light on the severity of mental health problems among Palestinian youth due to conflict. They emphasize the prevalence of mental health disorders like PTSD and highlight the urgent need for targeted mental health interventions.

Clinical Practice Implications: The findings underscore the critical need for mental health interventions that are tailored to the challenges faced by Palestinian children and adolescents in conflict zones. This includes enhancing access to mental health services and developing support systems that are culturally appropriate.

Economic and Social Impact: The blockade and recurring conflicts have not only caused psychological distress but have also severely impacted living conditions and economic stability in Gaza, making it difficult for people to lead normal lives and further exacerbating mental health issues.

Source:

Abudayya A (2023) Consequences of war-related traumatic stress among Palestinian young people in the Gaza Strip: A scoping review. Mental Health & Prevention. No 200305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2023.200305. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212657023000478.

Background

Elliott’s Part

History of Palestine

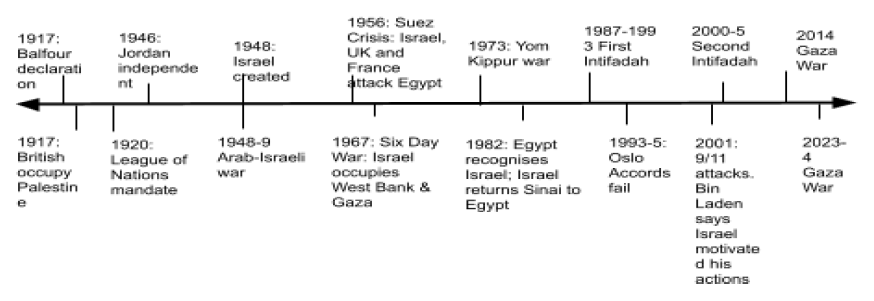

Short summary

The British promised Palestine to the Jews in 1917 without asking the Palestinians. In 1948 the British withdrew and the Jews set up Israel. Several wars followed, which the Arabs lost. Since 1967, all of Palestine has been ruled by Israel. Palestinians were supposed to get their own country, but this didn’t happen because negotiations with Israel failed. Palestinians are ruled today by Israel, but without most of the rights of Israeli citizens. Palestinians are frequently targeted for discrimination by the Israeli state. The latest Gaza war amounts to genocide, with Israeli politicians openly stating they want to kill all the Palestinians and take their land.

Some of the most powerful countries in the world continue to support Israel. The USA is blocking the UN

from doing anything to stop the massacre. Palestinians do not have a country, nor any army or government to protect them, nor do they have any chance of winning a fight against Israel. They do not have legal rights, nor can they leave. Unless the UN is reformed or Israel changes course, it is unlikely that the situation for Palestinians will

improve.

Historical background

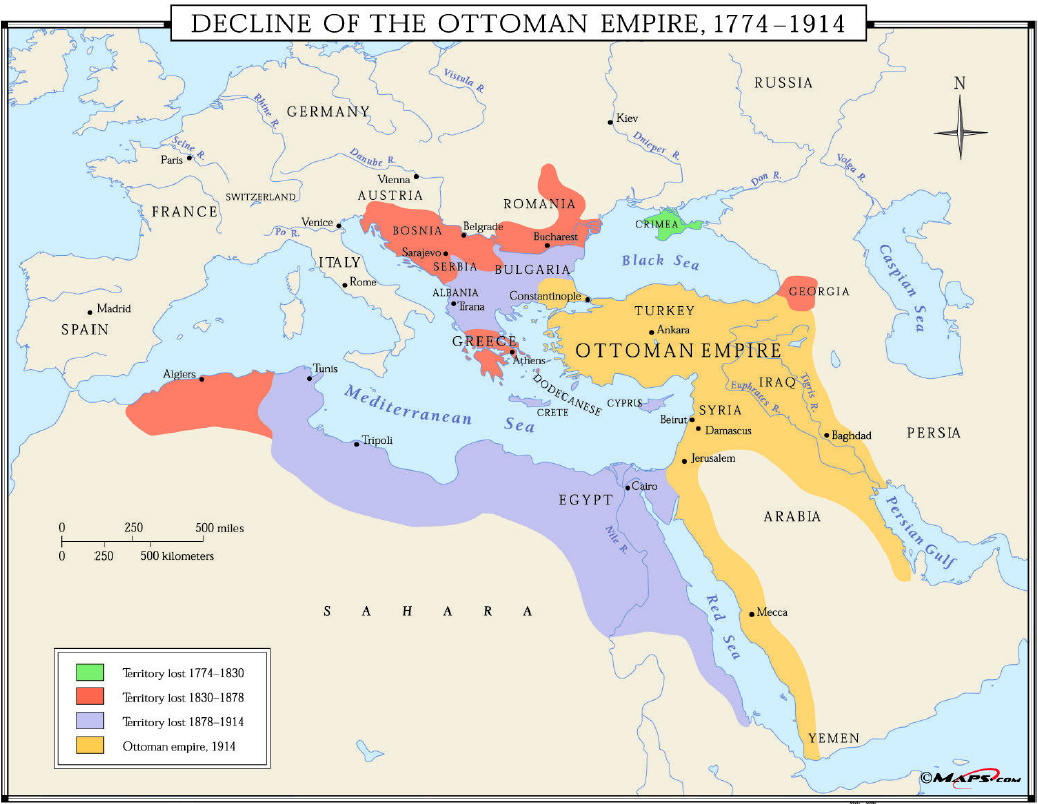

Palestine until 1917 was part of the Ottoman Empire for 400 years.

The Ottoman Empire was a Muslim-led state which contained many nations, but it was mainly ruled by Turks. Palestinians are Arab, but they do mostly share the same Muslim faith.

In the First World War (1914-1918), the Ottoman Empire lost against the British. This was the start of Palestine’s troubles.

In 1917, Palestine was occupied by the British.

- In 1917, the British government published the Balfour Declaration, which promised to establish a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

- The British did not ask the Palestinians whether they wanted to give their land to the Jews. The British just announced the decision, without the Palestinian people having any say in the matter.

- This is the root cause of the whole problem: the Palestinians never agreed to give their land to the Jews, nor were they ever asked for their opinion.

- Arthur Balfour made that promise to Lord Rothschild, a powerful member of the Zionist movement in Britain.

Theoretical framework

Elliott’s Part

Orientalism

One of the most relevant concepts that can be applied to the Palestinian people, and by extension Arab and Muslim cultures in general, is ‘Orientalism’, a term best explained by Edward Said in 1978. Orientalism can be defined as depictions of the Orient created in the west, usually for a western audience. Such depictions are often fantastical, frequently inaccurate, and usually demeaning at best and outright false or defamatory at worst. Orientalist tropes often include setting up the ‘east’ as inferior, uncivilised, immoral, effete, decadent, lacking in reason, and so on. Such works have a long history; for example, Orientalism is present in the depiction of Cleopatra and her court in the Shakespeare play Antony and Cleopatra, published in 1623.

Edward Said believed that Orientalism has negative real-world consequences, because Orientalist views tend to shape the attitudes and therefore the actions of western politicians and decision-makers. This has real, often negative, impacts in the real world. By constructing a false image by which people are placed under the category the ‘Other’ (Said, 1978, p1), Orientalist tropes dehumanise people, thereby making it easier to justify violence, hostility, discrimination and prejudice, and to justify the domination of the Orient by the West (Said, 1978, p3).

And this is precisely what we see, with the way the state of Israel has treated Palestinians, by systematically denying them rights, funding extensive propaganda to seed extremely biased and misleading news coverage in such a way as to disadvantage the Palestinians, and convincing people particularly in the USA and Europe that Israel should get a free pass on crimes against humanity while the Palestinian cause should be ignored, marginalised, even criminalised. For example, local councils in the UK were banned from supporting the peaceful BDS movement a few years ago.

Orientalist tropes often intertwine with racism and Islamophobia, to create racist and discriminatory imagery, language and attitudes towards Arabs, Muslims, and Palestinians in particular. This is particularly prevalent in western media, on the internet, and in discussions around the Israel-Palestine conflict. Politicians such as UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak described peaceful protesters marching for Palestine as ‘terrorist supporters’ and ‘hate speech’, for example. An outrageous falsehood, that is typical of the kind of prejudices that surround this issue. Such views are also common in right wing media, such as The Daily Mail, The Express, The Sun, and others, which have a long history of hateful racist ‘coverage’ of these kinds of issues. Much of this has been exposed by the ‘Hope not hate’ campaign, members of which have been viciously attacked and received personal threats from the newspapers, who don’t like their wrongdoing being exposed to scrutiny or criticism.

Orientalism often constructs the West as virtuous, superior, moral, disciplined, ordered, civilised, manly, rational. The Orient is the opposite of all these things: decadent, inferior, immoral, chaotic, self-indulgent, disorderly, barbarous, effete, irrational (Said, 1978, p7).

Source:

Said, Edward, 1978 Orientalism, published by Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Klaudia’s Part – The HEART

Human Rights

The concept of human rights, when analysed, has a rather vague conceptual grounding. However, human rights do have implications in ethics and are foundational to International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Numerous acts of legislation and legal conventions have been inspired by the notion of humanity’s inherent rights. For example, the “European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms”. These treaties and conventions may be seen as statements of ethical demands.

The International Human Rights Framework and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

In 1948, the United Nations (UN) established a human rights common standard by adopting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Since then, the UN has taken on several

binding international human rights agreements and treaties (for example, the “Convention of the Rights of the Child”). Such treaties provide a framework for the application of human rights. The outlined principles and rights become obligatory by law for those states who choose to commit to and be bound by them. As well, the framework implies legal consequences for states who infringe on human rights.

The mechanism of the international human rights framework consists of the UDHR and nine core human rights treaties (source: unicef.org):

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

- The Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

- The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Every country has ‘ratified’ (formally approved and sanctioned), at least one the nine treaties.

Human Rights Based Approach

The European Commission lists human rights as universal, indivisible, inalienable and interdependent. They apply to all of humanity, have equal importance, they cannot be taken away and can only be enjoyed by one if they are enjoyed by all.

The methodology of the human rights based approach (HRBA) is based on the international human rights framework and consists of five principles. These are “meaningful and inclusive participation and access to decision-making; non-discrimination and equality; accountability and rule of law for all; and transparency and access to information supported by disaggregated data”. Under these principles, states have a duty to protect, respect and fulfil individuals’ human rights.

Since ancient times, warfare has always been contingent upon principles and customs. International humanitarian law (IHL) applies to armed conflict only. Currently, Gaza is being subjected to a catastrophic humanitarian crisis. Around 25,000 people have been killed, 65,000 have been wounded and 1.9 of 2.3 million are displaced.

The IHL is the legal manifestation of the concept of human rights. The rules it outlines aim to limit the consequences of war. States and non-state armed groups maintain responsibilities during armed conflict. But, for the IHL to come to full effect during a conflict, passage for humanitarian aid must not be impeded, humanitarian workers need a guarantee of freedom of movement, and civilians, refugees, prisoners, the wounded and sick, as well as medical and humanitarian workers must be protected.

Healthcare in Palestine

No hospital in Gaza has been fully operational since the 19th of February and, of the facilities that are left, all have been entirely overwhelmed. The destruction of Gaza’s healthcare facilities has been intentional and has resulted in a monumental loss of life. The consequences of the war have meant an upsurge of infections from unsanitary conditions and overcrowding, as well as the interruption of urgent medical treatments. Only seven days after the beginning of war, 22 hospitals were ordered to evacuate by the Israeli occupation army and, on that very same day, the cancer diagnostics centre in al-Ahli Hospital was struck by an Israeli airstrike injuring four members of staff. Following this attack, Gaza’s northern hospitals were threatened with bombardment by Israeli army commanders. But, as they are providers of vital healthcare services, hospital staff decided that they would not evacuate.

October 17th saw the death of 471 Palestinians in the Israeli strike on al-Ahli Hospital. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) most recent report on the Gaza Strip, the oPt Emergency Situation Update (Issue 27), accounting for the time between 7th October 2023 and the 2nd of April 2024, has recorded that 10 out of 36 hospitals (28%) left are only partially functioning. Extremely high numbers of infections and outbreaks of diarrheal illness and hepatitis A. cases have been documented. The update reports 643,254 cases of acute respiratory infection, over 345,768 cases of diarrhoea, as well as thousands of cases of scabies, lice, chickenpox and acute jaundice syndrome. There have been 435 Health attacks, 30 hospitals damaged, 118 healthcare workers arrested and 100 healthcare facilities affected.

As the war progresses the increasing strain on the healthcare system continues to impact healthcare provision, access to life-saving services, and the distribution of essential medical supplies. Access to healthcare services is also hindered by damaged infrastructure, roads and restricted delivery of humanitarian aid. Seven members of the World Central Kitchen (WCK), which provides food relief in times of humanitarian crisis, were killed during an airstrike in a deconflicted zone in armed vehicles marked with the WCK symbol. So far it is calculated that 84% of total healthcare facilities have been damaged in the ongoing conflict. This has caused a detrimental shortage of medicine, ambulances, electricity, water and compromised essential health services. The Gaza strip is now facing an imminent risk of famine as 2.13 million people face ‘acute food insecurity’ (IPC Phase 3, which is considered ‘crisis or worse’.), and 677,000 people are already under ‘catastrophic food insecurity’ (IPC Phase 5). From January and thereafter, 28,180 children were screened for malnutrition and 22% were reported to be suffering from acute malnutrition. 25 children under five have died from dehydration according to MOH reports. Emergency Medical Teams have not been able to access northern Gaza and 9,000 critical patients are in need of medical evacuation. Furthermore, disruptions to telecommunications, displacement of staff and operational problems continue to impede necessary medical treatment in the Gaza Strip as the war continues. However, efforts are being made to supply the people of Gaza with healthcare needs such as medical supplies and food. 185 medical points across Gaza are providing essential care and 200,000 people are being given primary and secondary healthcare care every week.

Legal & International Law

Healthcare is granted protection under international law. Its continuous, targeted destruction in the Gaza Strip by the Israeli army is just one of many pieces of evidence brought to the International Criminal Court (ICC) recently to support the claim that Israel has committed war crimes.

In March of 2021, an official investigation into the situation in Palestine commenced. It was finally decided that the ICC could exercise its jurisdiction in both Gaza and the West Bank, which includes East Jerusalem.

However, despite an ever increasing body of evidence, the US continues to deny that Israel is guilty of any wrongdoing. On the 2nd of April 2024, John Kirby, the Spokesman of the White

House, claimed that the attack on the two World Central Kitchen (WCK) vehicles in which seven aid workers were killed was a mistake and continued on to state that the US has not found any evidence that Israel has violated international humanitarian law at all since the start of the war on October 7th.

An investigation conducted by Amnesty International into 229 deaths from unlawful airstrikes concluded that Israel is in violation of international humanitarian law. Since the onset of war, Israel has failed to distinguish military targets from civilians through indiscriminate attacks, failed to take reasonable measures to avoid injuring or killing civilians and has likely targeted civilians in its attacks. There has been no evidence that residential buildings could have been legitimate military objectives. Additionally, the Israeli army failed to provide sufficient warning in advance of the attacks. That is, if they provided any warning at all.

Last year, on October 9th 2023, Israel cut off all supplies of food, water, medicine and fuel to Gaza. Many residential buildings, healthcare facilities, schools and mosques have been destroyed in airstrikes, as well as other buildings where civilians have attempted to take shelter. Media

workers and medical personnel have also been attacked.

Israel has consistently ignored international humanitarian law. But, with the growing mountain of evidence, Israeli officials have been warned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that they may inevitably face prosecution by the ICC. The ICC deals with allegations of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. Separately, through the International Court of Justice (ICJ), known also as the World Court (the court of the United Nations), a genocide case was opened against Israel.

This case, filed in the Registry of the Court on the 29th of December by South Africa, requested proceedings against Israel on allegations of the violation of the ‘Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide’ (or the ‘Genocide Convention’). Additionally, the application requested the instigation of provisional measures with respect to the Palestinian people who are protected by the ‘Genocide Convention.’

According to The Institute for Palestine Studies, Israel has committed tens of thousands of war crimes, not only since October 7th 2023, but for the last 75 years. Israel has violated articles of the Geneva Conventions (1949), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Genocide Convention and International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Crimes which have a solid ‘foundational basis’ and may be brought before relevant courts in the future are, and this is a non-exhaustive list: genocide, intentional harm of protected persons, violation of treaties regarding vulnerable individuals, disproportionate response, forced displacement and land annexation, perfidy, desecration and mutilation of corpses, destruction of cultural property, and the illegal cut-off of food, medical supplies, and humanitarian aid in time of war.

Lucas’ Part

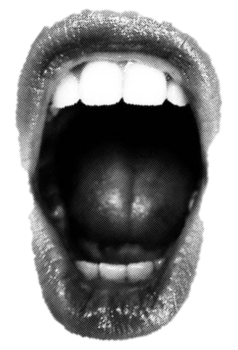

The Mouth on Freeing Palestine

1. Theoretical Framework: a postcolonial lens to the conflict in Palestine

When looking at the war perpetrated by Israel against the Palestinian people, it might be easy to side with the Israeli state and proclaim “Israel has the right to defend itself.” or “What is the proportional response to what Hamas has done against Israel in the 7th of October?”. Nevertheless, exploring the History of the conflict through a postcolonial view, it is clear that it is not a matter of response to what Hamas did, it goes back way longer than imagined.

This is why a post-colonial perspective on Palestine analyses the continuous impact of colonialism and imperialism in the Middle East. It takes into consideration how colonial powers, Britain especially, influenced the political, social and economic structures in Palestine, causing this never-ending conflict.

Dating back to the late 19th century, European nations started asserting control over parts of the Middle East including Palestine. This colonial action resulted in the establishment of Zionist settlements and the eventual creation of the Israeli state in 1948, which led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes.

The post-colonial perspective highlights the continuous effects of neocolonialism on Palestinian people, including military occupation, land confiscation and restriction of freedom and access to basic resources such as food. It examines as well the role of international actors, like the United States, in supporting Israel’s policies perpetuating the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

Additionally, a post-colonial view emphasizes the importance of decolonisation and self-determination, including the right to return for refugees and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. It challenges dominant narratives that justify the non-stop oppression of Palestinians and asks for a more just and equitable resolution to the conflict based on principles of human rights and obeying international law.

2. Zionism

For a better overview of why Israel has chosen this path, it is necessary to look at Zionism, which is the ideology driving the position held by the Israeli government in the

battle for the land of Palestine.

Firstly, it is important to tell what Zionism is: A political and ideological movement that emerged in the late 19th century (the same period as the nationalistic movements were rising all over Europe) to create a Jewish homeland in the historical land of Palestine, known by them as Zion, even Argentina was considered for this purpose and further rejected. It originated as a response to widespread anti-Semitism in Europe and the belief that Jews needed their own State. The movement gained traction under the leadership of figures like Theodor Herlz, who advocated for the creation of a Jewish state. Zionism drew inspiration from Jewish religious and cultural traditions, as well as nationalist movements of the time.

In its early days, Zionism was sometimes compared to fascism due to its emphasis on nationalism, exclusivity and the desire for a Jewish (religious) state. These comparisons were made inside the Jewish community, not only by outsiders. Critics argued that both movements prioritised the interests of a specific ethnical group or religious group and advocated for centralised control under a single leader or party. The aim of Zionism to establish a Jewish state in Palestine raised concerns about the rights of the indigenous people of Palestine, while fascist regimes targeted minority groups and promoted policies that excluded people based on race or ethnicity. However, it is important to recognise that the parallels between Zionism and fascism were distinct political movements with different objectives and the comparison between them still remains subject to debate.

Slowly and steadily, because of different circumstances, Zionism was turning into a consensus within the Jewish community around the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. This was driven by escalating anti-Semitism, the Dreyfus Affair, the advocacy of Theodore Herlz, Jewish settlement in Palestine, the Balfour Declaration and the tremendous impact of the Holocaust. All these historical events led many Jews to support the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine as a response to persecution and as a solution to the vulnerability of the community in the diaspora. By the mid-20th century, Zionism had become widely accepted in the Jewish community, which culminated in the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 (despite ignoring the importance of the land for the Palestinian people who have been living there for centuries).

Today, the Zionist movement remains active and diverse, advocating for Israel as the homeland for the Jewish people. It encompasses a spectrum of political and ideological views, shaping Israeli identity and policies. Zionist organisations worldwide promote solidarity with Israel and Jewish cultural identity. However, the movement faces criticism for human rights violations and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Despite challenges, Zionism continues to influence Israeli society and politics, impacting issues like security, settlement expansion, and peace negotiations. It remains a central element of Jewish identity and a source of debate within and outside the Jewish community, reflecting the ongoing complexities surrounding Israel’s historical and political significance.

2. International Reactions

Official Positions of the States involved in the conflict, all taken from their official websites, besides Hamas, which could not be found.

The position of the government can be resumed in a two state solution. Here is the Irish official position:

”(…) every Irish Government has given a high priority to the achievement of a two-state solution, which is now the accepted goal of all international efforts. The Middle East Peace Process remains a key foreign policy priority for the Government. Along with our EU partners, Ireland supports efforts to restart comprehensive negotiations for an overall peace agreement. (…)”

The EU wants to become more involved in the conflict and Israel should have the final saying on what solution will be adopted. The European Union official position:

”(…) No to the forced displacement of the Palestinian people. There cannot be an expulsion of Palestinians into other countries.

No to the amputation of the territory of Gaza or its reoccupation by Israel. There must not be a reduction of Gaza’s territory, permanent control of Gaza by the Israeli Defence Force, nor a return of Hamas to govern Gaza.

No to the dissociation of Gaza from the overall Palestinian issue. Our objective must be the resolution to the Palestinian issue as a whole.

Yes to the installation of an interim Palestinian authority in Gaza, under terms of reference and legitimacy defined by a unanimous and unambiguous resolution of the UN Security Council and guaranteed by it. We can think of a renewable resolution that encourages the two sides to reach an agreement, first for Gaza but then also for the West Bank.

Yes to a stronger involvement of Arab states if they agree, trusted by both the Israelis and the Palestinian Authority. Currently Arab states are not ready to discuss the day after the war. Yet, to achieve a lasting solution we need their commitment, which cannot be only financial. They must be certain that their involvement will not be an end in itself, but a step on a clear path towards a Palestinian state.

Finally, yes to a greater involvement of the European Union in the region. (…)”

In a resume, the UN wants two states and control over the humanitarian aid to Palestine. The United Nations official position:

An immediate ceasefire. Civilians and the infrastructure they rely on to be protected. The hostages to be released immediately.

Reliable entry points that would allow us to bring aid in from all possible crossings, including to northern Gaza. Security assurances and unimpeded passage to distribute aid, at scale, across Gaza, with no denials, delays and access impediments. A functioning humanitarian notification system that allows all humanitarian staff and supplies to move within Gaza and deliver aid safely. Roads to be passable and neighbourhoods to be cleared of explosive ordinance. A stable communication network that allows humanitarians to move safely and securely. UNRWA, the backbone of the humanitarian operations in Gaza, to receive the resources it needs to provide life-saving assistance. A halt to campaigns that seek to discredit the United Nations and non-governmental organisations doing their best to save lives.

Israel says they are acting according to the law and that they have the right to respond to the attack of Hamas. The Israeli official position:

”(…) The savage attacks perpetrated by Palestinian terrorist groups on October 7 and since then unquestionably constitute serious violations of international law, often amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity. They include the slaughter of over 1,400 Israelis and foreign citizens, the wounding of over 5,500, widespread acts of torture and maiming, burning alive, beheading, rape and sexual violence, mutilation of corpses, the abduction of at least 247 hostages (including infants, entire families, persons with disabilities, and Holocaust survivors), the indiscriminate firing of thousands of rockets, and the use of Palestinian civilians as human shields. Some of these crimes may also constitute genocide, as they are carried out with the “intent to destroy in whole or part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” in furtherance of Hamas’s declared genocidal agenda. Israel has the right, and indeed the obligation, to defend its citizens and territory by taking all legitimate measures to secure the release of the hostages and neutralize the threat it is facing. (…) Israel is simultaneously contending with ongoing attacks and threats emanating from other States and terrorist groups, including Iran and Iranian proxies such as Hezbollah. Hundreds of rockets, missiles and drones have been fired at Israel from Lebanon and Syria (…)”

The position of Hamas stated by intermediates:

”(…) Hamas wants a permanent ceasefire under which Israel will withdraw its forces from Gaza. However, Netanyahu has stated that he does not want to end Israel’s military campaign until a “total victory” has been secured over Hamas to which an invasion of Rafah is deemed key. (…)”

Action

Zahra’s Part

You can help by:

1. Taking action

Demand your elected representatives in Ireland speak out in solidarity to protect civilians and ensure humanitarian aid urgently gets into Gaza.

We need to say clearly that civilians should never be a target.

It is alarming that EU leaders are not calling more clearly for the protection of civilians and humanitarian access to Gaza. This is why we need all of our political parties in Ireland to call loudly and clearly on the EU to take greater action.

Sign our ROI petition: https://www.trocaire.org/petitions/demand-protection-civilians-gaza/

Sign our NI petition: https://www.trocaire.org/petitions/urgent-demand-protection-for-civilians-in-gaza-ni/

Gaza’s reality in numbers

- Gaza is already one of the world’s most densely populated pieces of land, with more than 2 million people crammed into 140 square miles.

- Almost half of the population in Gaza are children.

- Over 1 million Palestinians have been displaced.

- There are thousands of injured people in northern Gaza, elderly people, mothers with young children and other vulnerable people who will be unable to move from the area.

- There are multiple hospitals in Gaza City and in the north generally which cannot be evacuated without serious loss of life.

- Water, electricity, and internet have been cut off in Gaza.

- Humanitarian convoys of food, medicine, and other supplies necessary for the survival of the population through the Rafah crossing with Egypt have been limited.

2. Donate

Here’s a group you can donate to: https://www.ipsc.ie/support

3. Choosing your media wisely

Actively seek out articles written by Palestinians and Israelis.

Trócaire stands in solidarity with our partners in Palestine and Israel at this awful time. You can follow them for more information on the situation on the ground.

1. Al Haq – An independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organisation

Twitter: @Alhaq_org | Website: https://www.alhaq.org/

2. Palestinian Centre for Human Rights

Twitter: @PCHRgaza | Website: https://www.pchrgaza.org/

3. Gaza Community Mental Health Programme

Website: – https://www.gazamentalhealth.org/

4. Ofek – The Israeli Center for Public Affairs

Website: https://www.ofekcenter.org.il/eng/

5. Breaking the Silence – Breaking the Silence is an Israeli veterans’ organization aimed at raising awareness to the dire consequences of prolonged military occupation.

Twitter: @BtSIsrael | Website: https://www.breakingthesilence.org.il/

6. BADIL – Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights

Twitter: @BADIL_Center | Website: https://www.badil.org/

7. B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Centre for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories

Twitter: @btselem | Website: https://www.btselem.org/

4. Understanding the context

This major escalation did not happen overnight. Follow our partners above to help you understand the context and the events that led to this point.

Klaudia’s Part

Plan Development and Implementation

Action — Protest (and the BDS Movement)

There were many actions we could take for this project as a group. But, very early on in the process, we had all learned that, from 1-3pm in Grand Parade, the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign held protests for Palestine every week until the end of the war. Soon, we had organised a day when we could meet together in front of the Cork City Library and participate in the Palestine Protest.

At the time we didn’t have any supplies, no flags or signs, but we memorised the chants and raised our voices with the crowd as we all marched down St. Patricks Street, past the General Post Office and back onto Grand Parade. We remained there until 3pm, absorbing the speeches and music for Palestine. After the protest was over, 3 of us stayed behind the hopes of speaking to a member of the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, the speakers, artists, or a person from Palestine. We managed to discuss the current situation with two Palestinians who were kind enough to answer our questions. From these men we learned that the most effective and important action we can take is to participate in the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Movement (BDS movement).

Following the protest we began gathering information and resources: looking into the BDS movement, important news outlets, into the stories of Palestinians, both international and Irish public opinion, the history of the conflict and more. One of the most important sources we found were independent journalists operating on the ground in Gaza. Among these were Plestia Alaqad, Wael Al-Dahdouh, Motaz Azaiza, and Bisan Owda. The important list of resources was uploaded to Canvas for our classmates to access in their free time. Many of these resources should also be accessible on the website.

Out of all the actions we can take as individuals, the most salient is our participation in the BDS movement. Palestinians are entitled to the same rights as all other people. But there are several international and Israeli companies profiting from Israel’s war crimes. Participation in targeted consumer boycotts aimed at specific companies can make a significant difference. Currently, the Palestinian BDS National Committee (BNC) encourages the targeting of the following companies: Hewlett Packard (HP), Siemens, AXA, Puma, all Israeli Produce, SodaStream, Ahava cosmetics, and Sabra.

Targeted consumer boycotts have been very successful in the past. Starbucks and McDonalds, which are both companies linked to Israel’s war crimes, have been significantly affected by people’s increasing global solidarity with the BDS movement in 2023. The impact of the BDS movement continues to grow and has seen a lot of progress. Some examples of its effects are; Kuwait boycotting 50 companies linked to the occupation, Israeli ships being prevented from docking in ports around the world, European Union taking action against illegal Israeli settlements, Stephen Hawking boycotting an Israeli conference, and divestment by governments and banks.

Link to the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign website: https://www.ipsc.ie/

For more important visit the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Movement website: https://bdsmovement.net/

Benedetta’s Part – The SOUL

The SOUL – Art and Revolution

Arts, power and dissent

Art has a unique power to move and to persuade. When art is used against the established order in symbolic ways that form part of a resistance project, it shows all its intimate familiarity with power.

Creating art, be it in the form of posters, graffiti, or public artistic events, has historically been an effective way for a community to showcase their presence and determination in the face of established authority. Reclaiming public spaces by covering the walls and surfaces of city streets with symbolic messages is an act of defiance against authorities that seek to exert unchallenged control over such spaces. Those who challenge that control risk paying with their lives or freedom. The messages conveyed by the writing on the wall, images, and symbols signal alternative sources of authority, disrespect for established power, and its loss of control. By standing out for all to see, it shows the limits of governments’ influence and suggests the existence of a public that rejects the authority of those in power.

Moreover, the part played by artistic representation in all its forms constitutes another essential link with the politics of resistance. As with the writing and rewriting of history, the visual arts can harness the power of the aesthetic to sum up a narrative of identity and power. This narrative then can become a part of the collective memory and imagination, often supplanting or overshadowing thousands of individual memories, ultimately serving as a summation or epitome of historical experience. Established power has always used this technique; various forms of media, such as film and plastic arts, are used to create a shared visual representation that affects collective memory and promotes a specific version of the events. Resistance follows the same path. As with historical narratives written against the grain of power, so too can the power of art express a story suppressed and so give voice to the voiceless.

But why should people indulge in art during times of crisis and political urgency? According to Professor Roland Bleiker, aesthetic approaches can offer innovative ways to engage with representations of global social issues, thereby gaining political relevance by influencing how we perceive and construct our world (Bleiker, 2018). And here, we are not talking about politically committed art—the kind that promotes specific positions without adding significant aesthetic value—but artistic engagements that challenge fundamental perceptions and representations of power.

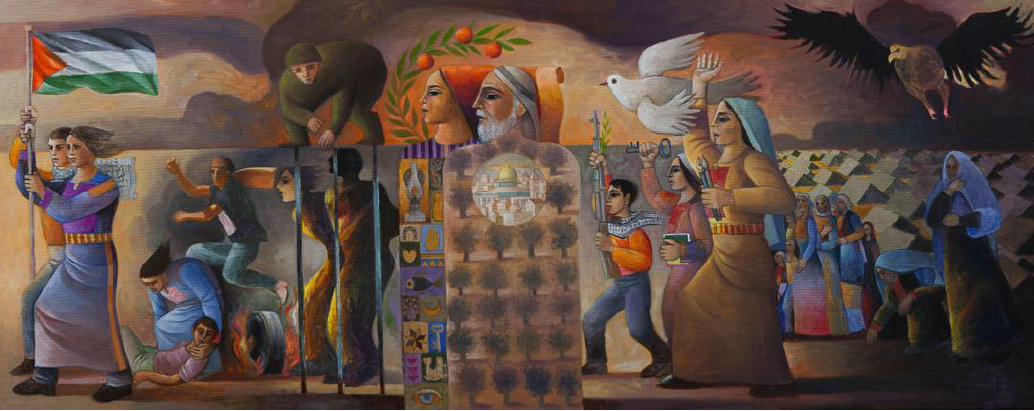

Truly aesthetic political poetry questions how political issues are internalised in our collective consciousness rather than just addressing specific problems. Palestinian resistance art is an excellent example of this.

Palestine’s Cultural Production: The Art of Resistance

Palestinian cultural production historically represented and shaped a national identity struggling to survive.

The Intifadas of the 1960s and 1970s saw the birth of what many now consider classical Palestinian art forms, such as Ghassan Kanafani’s literature, M. Darwish’s poems, and Suleiman Mansour’s paintings (Salih & Richter-Devroe, 2014). All three authors were actively part of the political landscape and the Palestinian struggle, embodying the deep connection that often exists between art and politics.

Ghassan Kanafani portrays the complex dilemmas Palestinians of various backgrounds must face. Kanafani set a literary trajectory in which the exile is stripped of its physical form, from an actual denial of return to the homeland to an ethereal and deeply psychological existence of exclusion, marginalisation, and memoricide. He was the first to deploy the notion of resistance literature (“adab al-muqawama”) concerning Palestinian writing, encouraging a specific aesthetic for the armed struggle in his texts.

Mahmoud Darwish’s poems often trace themes of exile, identity, justice, and freedom. In them, he employs iconic images such as olive trees, jasmine, wounds, and rocks to symbolise the Palestinian struggle. The Palestinian people widely recognise and celebrate these symbols as they represent a shared consciousness of their fight. Darwish’s poetics reflect both personal and collective experiences, blending modern and traditional themes.

Suleiman Mansour’s paintings. He has tailored his comprehensive portfolio around the Palestinian struggle, restating the Palestinian story by incorporating traditional and new symbols into his art. During the first Intifada, Mansour and other artists found the ‘New Vision’, an art movement to boycott Israeli art supplies and instead utilise local natural materials like mud and henna in their work. Mansour’s work features several symbols associated with the Palestinian struggle, such as the Jaffa orange, the olive tree, or the dove.

Art can be a powerful form of dissent in less explicit ways than open demonstrations. Professor of Politics C. Tripp suggests three primary links between artistic interventions and the politics of resistance. Firstly, artistic interventions serve as a means to challenge and question the existing political hegemony and the established power structures. Artists can question and resist the status quo by creating works that provoke thought and elicit reactions, potentially leading to re-evaluating power dynamics. Secondly, art shapes collective identity and memory by offering different narratives or perspectives that may conflict with the dominant discourse. Finally, art can mobilise individuals and communities to unsettle and undermine claims of authority, a crucial aspect of the politics of resistance. For instance, Palestinian resistance art uses cynical and humorous tones to engage with the harsh reality of living under siege, focusing on the paradoxes of daily life during the occupation. Irony is employed as a vernacular and subversive instrument to ridicule the occupiers and represent the reality beneath the one imposed on them. One of the main examples of this genre is Elia Suleiman’s semi-autobiographical film The Time That Remains, in which Palestinian historical events are portrayed through detachment, irony, and black humour.

Street Art as a Form of Activism

Since the First Intifada, creating visual portrayals that describe and reflect on various aspects of the Palestinian problem has become common practice. It is important to emphasise the significance of street art, as it plays a central role in Palestinian Resistance and serves as a key instrument in Palestinian civic and political activism.

During the uprising of 1987/1991 in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, graffiti became a symbolic act of defiance: “You could show your commitment to the cause by going out at night with a paintbrush or a spray can” (Peteet, 1996).

Beyond its symbolic meaning, street art holds importance in reclaiming public space from those in power, whether political leaders or military occupiers. By painting messages of resistance on walls and buildings, individuals assert their presence and challenge the dominance of authority figures in these spaces. While realising the Zionist project of creating a nation-state, one of the first attempts by the new authorities was to build a Jewish art scene, which was pitched towards the goal of strengthening the national spirit. The broad objective was to represent the territorial space in a way that would reinforce the Zionist political imagination. This imagination manifested itself in places like Jerusalem, where, for example, architectural decorations were undertaken following political and visual/aesthetic requirements. Due to the discomfort felt towards Palestinian artworks, Israeli authorities resorted to restrictive measures such as censorship and prohibition of exhibitions.

In some cases, however, like the construction of the Separation Wall in the West Bank, Israel itself inadvertently created massive surfaces ripe for art. This expansion of available space provided an opportunity for graffiti artists to express dissent and resistance against the Israeli occupation and assert Palestinian identity in the territory.

Palestinian visual arts are used to undermine occupation by painting murals that contain symbolically powerful images in public spaces. One of the most iconic ones is the graffiti of the militant Leila Khaled, who is considered a heroic figure in the Palestinian tradition of resistance due to her actions as a member of the PFLP, especially during the Seventies.

Given that power is a fungible concept and that it may be as much material as immaterial, the symbolism that permeates Palestinian art clearly, simply, and impactfully announces Palestinians’ aspirations, including, first of all, the recovery of their inherent rights over the historic land of Palestine.

For instance, the symbol of a key signifies Palestinian uprootedness as well as also Palestinians’ determination to acquire the right of return. Another example is the watermelon, which has evolved into a symbol of resistance in occupied Palestine because its colours resemble the Palestinian flag. In response to the Israeli government’s ban on displaying the flag, in fact, Palestinians subtly expressed their national pride through watermelon imagery.

Another powerful symbol is Handala, a cartoon character created by the political cartoonist Naji al-Ali, painted over and over on walls, canvas, t-shirts and tattoos. The image still lives to this day as a profound symbol of defiance and identity for all Palestinians, even long after al-Ali’s assassination in 1987. Handala is a ten-year-old child – because that was the age al-Ali was when he left his homeland – and will remain ten years old until he is allowed to return home, at which point he will begin to grow up.

The importance of artworks during this struggle is evident since the iconic symbols rooted in Palestinian street art tradition can best be understood as political artefacts rather than descriptive illustrations.

In fact, street artists in Palestine aim to inspire hope and resistance in the struggle for liberation. However, their depictions of Palestinian reality are influenced by their own cultural and ideological backgrounds. This often results in artwork that clashes with that of other groups, highlighting a deeper issue: the presence of internal divisions within the Palestinian community. This problem undermines the effectiveness of the Palestinian struggle. Due to ideological differences among Palestinian factions, the street art scene is often populated by competing visual representations. Expectedly, signs and symbols suffusing street artworks reflect artists’ and groups’ own politico-ideological orientations. For instance, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a secular left-wing group whose street art bears images of workers, citizens, and fighters, uses the image of Leila Khaled in their visuals. Moreover, the messages of PFLP often read, “We salute the women of the intifada – PFLP” (Peteet, 1996). Such messages are directed against conservative Palestinian movements that seek to promote religion-based gender stereotypes. For example, the message “Morals or else. . . – Hamas” (Peteet, 1996) indicates a religiously oriented discourse in street art, which is also manifest in religious groups’ use of “Islamic symbols” and “Qur’anic quotations” in their visuals (Tripp, 2013).

Banksy and International Involvement in Palestinian Art

Street art in Palestine also draws support from international artists, such as the British muralist Banksy, who is known for his political activism through his absurd and dystopian pieces. He has worked extensively in Palestine in the last two decades, and his murals on the Separation Wall have attracted considerable international attention due to comprehensive press coverage. Still, they are also a perfect example of the controversy around the public’s reception of artistic creations.

In August 2005, Banksy travelled to the West Bank and Gaza Strip. As a mark of protest, he created a series of images on the Palestinian side of the West Bank Wall, the 700-km-long separation barrier erected by Israel. The International Court of Justice declared the Wall illegal in 2004 and ordered dismantling. Still, it was not, and it became the site of colourful graffiti with messages and slogans in English and Arabic. Nine graffiti pieces belonged to Banksy, drawing tourists worldwide; the world only truly began to listen after it first could look.

In the first mural, the man’s posture indicates a violent intention. However, Banksy promotes peace instead of violence by making him hold a bouquet. The flowers in this image represent not only peace or love but may also serve as a tribute to the lives lost during the old era of religious conflict.

“Flying Balloon Girl” is perhaps the first piece of West Bank Wall graffiti art to have received international acclaim. In its original context, the artwork might refer to the Palestinian right to freedom of movement and possibly to the right to return. It has been described as: “poignantly simple”, with its message “as essential as the artwork: through magic realism and notions of childhood innocence, the young girl embodies a dreamy, supernatural hope as the balloons lift her from her stark surroundings” (Lennon, 2022).

In Addition, Banksy owns a boutique hotel in Bethlehem called ‘The Walled Off Hotel’, nestled against the Wall dividing Israel and Palestine. A genuine place to stay, the hotel is also a symbol of protest and an exhibition of his artwork. It has a museum and art gallery that also showcases the works of other Palestinian artists. The hotel has shut operations currently due to the war situation with Israel.

The West Bank Wall: An Aestheticization of Pain or a Protest?

Among Palestinians, reception to the barrier’s artwork is mixed. Some locals have expressed a positive view of the Separation Wall’s transformation into an attractive graffiti site: “The battle against the occupation has shifted from committees to media sites. The images of the [separation] wall often speak louder than politicians’ voices” (Au—Larkin, 2014).

However, some locals consider the graffiti an aestheticisation of their suffering. Banksy recalls his first visit to the West Bank Wall, during which an old Palestinian man told him that his painting made the Wall look beautiful. After Banksy thanked him, the man replied, “We do not want it to be beautiful, we hate this Wall. Go home.” (Bansky in Salih & Richter-Devroe, 2014).

This is why some artists focus not on promoting international awareness but on supporting Palestinians. In 2007, Palestinian artist M.A. Hamid spray-painted a 14-meter-long mosaic of random Arabic letters. When unscrambled, however, these letters spell out the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence. Because the piece’s location is in an area where virtually only locals would come across it, Hamid defines it as a message of hope for Palestinians and them alone.

In this context, the impact is complicated to measure. Plausibly argue that visuals that find resonance beyond Palestine would afford Palestinians a stronger connection with the outside world. Street art on the Israeli Separation Wall ignores its history as a borderland and normalises the Wall’s fetishisation by using it as a canvas. While graffiti on the Wall has attracted international tourism, visitors who appreciate its newfound aesthetics often do so without considering its negative impact on the lives of locals directly affected by it.

However, even before the construction of the Separation Wall or Banky’s activity, there had long been a culture of “writing on the walls” in Palestine. Graffiti on the West Bank Wall has become a popular art form for both local youth and professional artists. It has also become a revolutionary act of resistance, sparking critical discussions about the Wall’s existence and what true peace in the area should look like. This form of public and accessible expression has gained international attention and has invited people to think deeply about the issue. Israel has attempted to impede Palestinian artistic activity through security measures and sought to cultivate an image of the newly settled territorial space under its own political vision. This observation implies that within the mechanisms of censorship lie the tools for its potential undoing— a notion evident upon scrutinising any censorship regime. Artistic endeavours, particularly those necessitating the freedom to articulate their unique voices, often find themselves at the forefront of resistance movements, initially focused on securing the necessary space for expression. The content of these artistic messages can vary widely, ranging from explicit condemnations of prevailing political regimes to more nuanced attempts at challenging ingrained societal values and conventions, thereby disrupting the comfort of everyday routines. Nevertheless, irrespective of the form, the mere act of disseminating ideas that diverge from conventional wisdom, cultivating an audience receptive to alternative perspectives, signals a perceptible shift in power dynamics. This transformative process highlights the resilience of art as a catalyst for societal change and underscores its capacity to challenge established power structures.

Lucas’ Part

Action plan

The group was really diverse in its background: Two people coming from Arts (music production and creative arts), an English teacher, a pharmacologist and a sustainability student. The group reunited the best of the abilities each of the members brought and came up with a creative material to inform students of Global Citizenship Development Education about the conflict in Palestine.

Initially the group reunited to discuss the role allocation and the members picked what they would research themselves. And the subjects researched were: Palestine refugees, the role of UNRWA, the History of the conflict, cities and towns, psychological impact of the conflict on the well-being of Palestinians, media content to inform yourself about it, the History of Palestine, Orientalism, Human Rights, Healthcare in Palestine, Legal & International Law, the BDS Movement, Palestinian Cultural Production, Street Art as a form of activism, Post-colonialism, Zionism and International Reactions.

Afterwards, the group decided to join the ongoing protest occurring in cork City to learn more about the topic and meet Palestinian people to explore their point of view on the conflict, but most importantly, to listen to their stories and how they are being affect by it and ask for recommendations on the issue.

Throughout the project, it became clearer how educators can use the topic to educate students on it. It is important the historical context of it, otherwise it will lead to an uniformed learning that does not take into consideration the whole picture. The conflict highlights the important and necessity of Human Rights and social justice issues, the educator can explore the effects of the displacement of the Palestinians and how this can happen with anyone (even more when we are threatened by climate change). Besides needing multiple perspective and empathy to look at it from different point of views. More importantly, it is definitely an opportunity to work on peacebuilding and conflict resolution through knowledge and dialogue and how wars do not lead to peace, it leads to destruction.

Finally, educators can use the conflict about Palestine as a case study to foster global citizenship and solidarity with marginalized communities worldwide. By connecting local issues to global contexts, educators can empower students to take action for positive social change and human rights advocacy. Overall, educators can use the conflict about Palestine as an opportunity to engage students in critical inquiry, ethical reflection, and dialogue about complex issues of identity, power, and justice. By fostering empathy, critical thinking, and a commitment to social justice, educators can empower students to become informed, engaged, and compassionate global citizens.

Reflections

Palestine protest

Date: Saturday 24 February 2024

Location: Cork

Event type: Palestine protest march

Which of us were there: Elliott, Zahra, Lucas, Klaudia.

Palestine protest reflections

Elliott

I attended this event because I have been a supporter of a free Palestine for many years. This topic is close to heart for me, because of my close friendships with people from Arab/Muslim background over the past 14 years. I attended a protest about the war in Gaza in 2014, but had lost touch a little with this topic in recent years. Part of it was exhaustion – it can be emotionally hard to manage feelings about conflict, humanitarian disasters, and also the toxic online ‘debate’ that makes it stressful to engage at times. But I felt that this was an important topic and, out of the many Global justice issues out there, this one is one of the most powerful to me personally.

My feeling about the event was a combination of hope, depression about the state of the world, sympathy for the victims, and also uncertainty. For me one of the big things that stood out was how much things hadn’t changed in 10 years, from 2014 to 2024. Many of the slogans used in the march were the same ones I remembered. However, there were new ones as well – I noticed with interest the long list of politicians that were criticised! Including Emmanuel Macron, David Cameron, Joe Biden, Benjamin Netenyahu, Ursula von der Layen, and others. I was also inspired by the high-quality of the speakers – there were representatives from the trade union movement in Ireland, some interesting references to Irish history and Ireland’s struggle for freedom from colonialism. I also do feel proud that Ireland is a country that sides with the oppressed, against the oppressor. I lived in the UK for many years and while a lot of people there do support Palestine too, the news media in that country and the government, are more pro-Israel. I feel proud of Ireland for calling out the genocide for what it is.

I learned more about the details of the suffering of people in Palestine. I hadn’t been following the news at all since October (because I knew I would get upset/angry). However, this event was more uplifting than the standard news media. There were songs, speeches, and personal stories. I also spoke to some of the Palestinian people attending this event at the end. One man told me about how one of the problems for Palestinian people is the economic situation. There is high unemployment in the occupied territories, and for many Palestinians the only job is working on building illegal Israeli settlements on their own land! The Palestinians face a terrible dilemma in that situation, which puts their own survival as individuals against the future integrity of their homeland. I also became more aware of the ways in which the United States of America is supporting Israel (e.g. with billions of dollars in military aid), the way Joe Biden is complicit in the genocide, and the way in which even the European Union and even the Irish state do not have a completely clean record.

Klaudia

I can’t say that I enjoyed the protest. Being there felt empowering, and it was the second time I had attended a protest that large (the last one being the Climate protest a few years back), but until that day I had only really seen major acts of solidarity and protests online. And, though I was happy to participate, all I could think about as I walked were the images and videos I had seen of the devastation in Gaza. Videos and images of mothers crying for their dead children, of people searching through rubble for survivors, shrouds, horrific injuries, children with missing limbs wrapped in stained bandages. Looking around at the sign that the people there were holding only reminded me of that. However, my presence there felt necessary, and I regret not attending more protests over the last months. I felt so small at first. But, when everyone started marching down the first street and chanting ‘Free, free, Palestine!’, all our steps and voices blended together as if there was no distinction. I felt, again, that I was part of something greater than myself. Seeing massive protests in clips online is one thing, but actually participating in one is an entirely different experience. I felt angry, I felt small, I felt awful, and then I felt empowered and so proud of everyone. Knowing that this was one protest out of so many around Ireland and around the Globe was reassuring. Again, I only regret not having attended more of them in the past.

Zahra

It’s been beautiful to see so many people show up week after week in Cork city and show they stand up for Palestine and humanity.

Whenever I feel like this is world is doomed and lose all hope I try to surround myself with likeminded people, you may think it’s exhausting to go to the protests but I can assure you that if the cause resonates with you in anyway showing up in these protest you will go home fully refreshed and rested.

Reflection on Group Organisation (Elliott)

As a group we organised ourselves using the following methods:

- We organised a team WhatsApp group to discuss our project, timeline and responsibilities.

- We arranged to meet up three times independently of class. Twice to discuss our project and once to attend a Palestinian protest march in Cork.

- We assigned different responsibilities to each member of the team.

- We shared resources and helped each other to understand the requirements of the course.

This plan worked reasonably effectively. Each member of the team contributed to the skills and topic areas that suited them best.

The different focus areas included:

- Art

- History

- International relations

- Project design & presentation

- Palestinian voice

In our planning sessions, we mapped out the five different assignments that each of us should complete. This allowed us to further refine our approach. For example, I chose to support our critical theory approach by addressing the topic of Orientalism, as set out by Edward Said in his landmark 1978 book of the same name.

We attended the protest on 24/2/2024, which is discussed separately in our group reflection.

Our objective was to present knowledge and information about the experiences of the Palestinian people. We also aimed to support the Palestinian protest movement, with the goal of mobilising public support for a ceasefire in Gaza.

Content delivery was relatively decentralised, in the sense that each member of the team was delegated to complete their tasks and given the space and opportunity to do so. Responsibility within the team was for each individual to manage their own work in line with the deadlines for the project, in particular the presentation on 16 April.

Some members of our group were able to attend a practice run in advance of 16 April, which helped to finalise the material necessary to present to the class.

This project benefitted from clear communication, collaboration and spheres of responsibility.

Possible criticisms/areas of improvement: It is difficult

with an issue as large and intractable as the Palestinian conflict to avoid frustration at the global nature of the situation and the feeling that perhaps we could have done more in some way. Our group shared resources that would enable people to support Palestinians affected by the conflict. However, it’s possible that future groups might take a more concerted look at how action can lead to impact in a manner that moves this issue forward as much as possible. Our group did have some ideas such as producing flyers or engaging with student radio. But ultimately not all ideas were carried forward, in part due to time pressures and the needs of conflicting course assessments. Starting earlier might also have been helpful to alleviate some of these issues, although on balance I do feel that our group was fairly proactive from the outset. More time in class focusing on the projects might have been time well-spent, as focusing on other topics left relatively little time for understanding the scope of our project until a relatively late stage.

Benedetta

Art can seem like a luxury, an absurd disconnect from reality in times of war. However, it is no coincidence that colonialism has always used the systematic cancellation of indigenous cultures as a tool to make its own narrative prevail. And then art becomes an affirmation of life that emerges from the grey of ruins. The works of artists who for years have been trying to find the means of expression to represent and preserve their identity in a place where that identity is confined behind walls and checkpoints are the answer to the question of what the point is of picking up a pen instead of a rifle. We are not all born fighters, and often, colours and shapes go further than a bullet, as evidenced by the involvement of dozens of international artists who, although controversial, are still a megaphone through which Palestinian people can shout and reclaim the fundamental rights of human beings.

Since Cork regularly hosts demonstrations in favour of Palestine and is also rich in street art, I wondered if there could be signs of the famous street art that has decorated Palestinian places for years. Walking through the city streets, I actually found signs of this non-violent resistance:

Considering what has been said and experienced so far, I am inclined to say that the intersection of art and resistance in the Palestinian struggle is a powerful reminder of the enduring human spirit and the universal pursuit of justice. It is a testament to the power of creativity and solidarity in the face of oppression, inspiring hope for a future where freedom and dignity prevail for all.

Lucas

This protest was the first one that I have been to and it was surprisingly positive to see how many people were there in the protest, not only people from the Middle East or Muslims, but mostly Irish people and other immigrants.

I attended this event because I wanted to understand the reason why people were protesting, although being initially obvious. Also, to be more aware of the issue itself due to fact that the conflict has always been viewed from an Israeli perspective when I was growing up and being educated in Brazil. We used to see Muslims as the terrorists (personally, it started after the 9/11). My will was to become less biased towards the issue and come up with ideas on how to help Palestinian people being so distant.

I definitely did not feel comfortable initially thinking about the images I have seen on the internet where troubles always rise in protests, but it was more peaceful than expected, despite not being a peaceful topic. I remember all the chanting “Be free, PALESTINE!”, how angry the woman was when singing it and this anger kind taking over me as it is hard to agree with anything being done to Palestinian People. I remember kids being there as well as old people.

As the protest were heading towards the end, it is hard not to be moved by what is happening in Palestine and is becomes clearer that this issue is not something new, that it started only 6 months ago. Additionally, I have learned also how Irish people do stand in solidarity to Palestinians, even the politicians stand their voice in the Irish parliament. It also become known to me the companies standing with Israel in the conflict. But the main lesson is: How intersectional this conflict is… So many different issues can be taken from only this conflict and honestly, I am not hopeful for the people of Palestine, even though I want them to become an independent state recognised by the international community.

Bibliography

1. Theoretical framework – Human Rights

Sen, A., 2017. Elements of a theory of human rights. In Justice and the capabilities approach (pp. 221-262). Routledge. Available at: https://jenni.uchicago.edu/WJP/papers/Sen_2004_v97_n4_elements.pdf

European Commission, no date. The Human Rights Based Approach (HRBA). wikis.ec.europa.eu. Available at: https://wikis.ec.europa.eu/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=50108948

UNICEF, 2019. The International Human Rights Framework. www.unicef.org. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/armenia/en/stories/international-human-rights-framework#:~:text=The%20instruments%20of%20the%20international,Economic%2C%20Social%20and%20Cultural%20Rights

ICRC, 2022. What is International Humanitarian Law? icrc.org. Available at: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/what_is_ihl.pdf

United Nations, 2024. “Gaza is a massive human rights crisis and a humanitarian disaster”. ohchr.org. Available at:

https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2024/01/gaza-massive-human-rights-crisis-and-humanitarian-disaster

European Commission, no date. International Humanitarian Law. civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu. Available at:

https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/humanitarian-aid/international-humanitarian-law_en

2. Theoretical framework – Healthcare in Gaza

International Rescue Committee (19th March 2024) www.rescue.org. Available at: https://www.rescue.org/eu/article/collapse-gazas-health-system

Moolla, M.S. and Jacub, A., 2024. Healthcare and genocide: BDS as an entry point to health justice. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 17(1), pp.1-2. Available at:

https://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S1999-76392024000100001&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Saad, H.B. and Dergaa, I., 2023. Public health in peril: assessing the impact of ongoing conflict in Gaza Strip (Palestine) and advocating immediate action to halt atrocities. New Asian Journal of Medicine, 1(2), pp.1-6. Available at: https://journals.kmanpub.com/index.php/najm/article/view/1518

Abed Alah, M., 2024. Echoes of conflict: the enduring mental health struggle of Gaza’s healthcare workers. Conflict and Health, 18(1), p.21. Available at:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13031-024-00577-6

Moolla, M.S. and Jacub, A., 2024. Healthcare and genocide: BDS as an entry point to health justice. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 17(1), pp.1-2. Available at:

https://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S1999-76392024000100001&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Soni, A., 2023. Israel desecrates the sanctity of healthcare with its attacks. South African Journal of

Bioethics and Law, 16(3), pp.1-2. Available at:

https://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S1999-76392023000300001&script=sci_arttext

Hanbali L (2024) Israeli necropolitics and the pursuit of health justice in Palestine. BMJ Global Health, vol 9, issue 2, e014942. PMCID: PMC10836346. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10836346/

Selcer R (2023) Settler Colonialism and Health in Palestine: A Call to Action. Health and Human Rights Journal. 20 December 2023. [Online]. Available at: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2023/12/palestine-health-and-settler-colonialism-a-call-to-action/

3. Theoretical framework – Legal and International Law

Hanbali, L. 2024. The Destruction of the Health Sector in the Gaza Strip. Institute for Palestine Studies, pp. 1-9. Available at: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/1655249

International Criminal Court., no date. State of Palestine. icc-cpi.int. Available at:

https://www.icc-cpi.int/palestine

Al Jazeera., (3rd April) 2024. US says Israel has not violated international law during Gaza war. aljazeera.com. Available at:

https://www.aljazeera.com/program/newsfeed/2024/4/3/us-says-israel-has-not-violated-international-law-during-gaza-war

Amnesty International., 2023. Israel and Occupied Palestinian Territories 2023. www.amnesty.org. Available at:

https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/middle-east-and-north-africa/middle-east/israel-and-occupied-palestinian-territories/report-israel-and-occupied-palestinian-territories/

Amnesty International., 2024. Israel/OPT: New evidence of unlawful Israeli attacks in Gaza causing mass civilian casualties amid real risk of genocide. www.amnesty.org. Available at:

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/02/israel-opt-new-evidence-of-unlawful-israeli-attacks-in-gaza-causing-mass-civilian-casualties-amid-real-risk-of-genocide/

Al Jazeera., (29th April) 2024. Israeli officials eye threat of ICC arrest warrants over war in Gaza. aljazeera.com. Available at:

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/29/israeli-officials-eye-threat-of-icc-cases-over-war-in-gaza

International Court of Justice., 2024. Summary of the Order of 26 January 2024. icj-cij.org. Available at: https://www.icj-cij.org/node/203454

Sayegh, N. 2023. No Justice, No Peace: A List of Israeli War Crimes Since Oct. 7. Institute for Palestine Studies. Available at: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/1654922

4. Theoretical framework – Postcolonial lens

Al Jazeera. “Biden Says Israel-Hamas “Ceasefire” Imminent: What Could a Deal Look Like?” Al Jazeera, 27 Feb. 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/27/biden-says-israel-hamas-ceasefire-imminent-what-could-a-deal-look-like. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Amar-Dahl, Tamar. Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 7 Nov. 2016.

Ato Quayson. Postcolonialism. Polity, 4 Jan. 2000.

Borrell, Josep. “What the EU Stands for on Gaza and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict | EEAS.” Www.eeas.europa.eu, 15 Nov. 2023,

www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/what-eu-stands-gaza-and-israeli-palestinian-conflict_en. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Department of Foreign Affairs, An Roinn Gnothaí Eachtracha. “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” Ireland, 2024, https://www.ireland.ie/en/dfa/role-policies/international-priorities/israeli-palestinian-conflict/. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Hamas-Israel Conflict 2023: Key Legal Aspects.” Gov.il, 7 Oct. 2023, https://www.gov.il/en/pages/hamas-israel-conflict2023-key-legal-aspects#ANNEX%202. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

United Nations. “Israel-Gaza Crisis.” United Nations, 2024, https://www.un.org/en/situation-in-occupied-palestine-and-israel#:~:text=Learn%20More-. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Smith, Gary V. Zionism. Barnes & Noble Books, 1974.

General references

Adamolekun, D. (2022, August 19). From piece-making to peacemaking: The influence of West Bank barrier graffiti art. Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/from-piece-making-to-peacemaking-the-influence-of-west-bank-barrier-graffiti-art/

Alim, E. (2020). The art of resistance in the Palestinian struggle against Israel. Türkiye Ortadoğu Çalışmaları Dergisi. https://doi.org/10.26513/tocd.635076

Anas, A. (2007). Ethnic Segregation and Ghettos. In A Companion to Urban Economics (pp. 537–554). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Au – Larkin, T.-. J. (2014). Jerusalem’s Separation Wall and Global Message Board: Graffiti, Murals, and the Art of Sumud. XXII JO – Arab Studies Journal ER, 1, 134–169.

BDS movement. bdsmovement.net. Available at: https://bdsmovement.net/impact

Bleiker, R. (2009). Aesthetics and world politics. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Jo, H., Dvir, R., & Isidori, Y. (2016). Who Is a Rebel? Typology and Rebel Groups in the Contemporary Middle East.

Lennon, J. (2022). Conflict graffiti: From revolution to gentrification. University of Chicago Press.

Peteet, J. (1996). The writing on the walls: The graffiti of the intifada. Cultural Anthropology: Journal of the Society for Cultural Anthropology, 11(2), 139–159. http://www.jstor.org/stable/656446