IDEA Conference 2022 – Development Education and Conflict Blog

This blog was written by Zelalem Sibhat (Lecturer in Mekelle University, Tigray, Ethiopia), Gerard McCann (Senior Lecturer in International Studies and Head of International Programmes at St Mary’s College, Belfast) and Gertrude Cotter (Lecturer at the Centre for Global Development, UCC) who facilitated a workshop called ‘War, Peace and the future of Development Education’ at the IDEA conference on Wednesday 23 June 2022. The blog was first written for IDEA but reproduced here. Below they each share personal reflections on the different elements of their workshop.

Reflections from Gertrude Cotter

I introduced the theme of war and peace by showing images of where there is ‘war’ in the world. Looking at the map, one participant astutely said ‘I see colonialism in that map’. My own view is that colonialism is the key root cause of many of the issues we deal with in GCDE.

I introduced the theme of war and peace by showing images of where there is ‘war’ in the world. Looking at the map, one participant astutely said ‘I see colonialism in that map’. My own view is that colonialism is the key root cause of many of the issues we deal with in GCDE.

My input primarily raised questions. For instance, why is the word ‘war’ not to be found anywhere in the Sustainable Development Goals document? Why, with 8 years left to achieve the SDGs, do we find the following facts at the Global Peace Index and United Nations sites?

- Between 2008 and 2021, the level of global peacefulness deteriorated by 2%. Since 2008 there has been increased political instability worldwide.

- According to the Global Peace Index:

- Conflict in the Middle East has been the key driver of the global deterioration in peacefulness since 2008; deaths from external conflict recorded a sharp deterioration driven by the Russian invasion of Ukraine; the rise in costs has increased food insecurity and political instability globally, with Africa, South Asia and the Middle East under greatest threat; the political terror scale, political insecurity, neighbouring country relations, refugees and IDPs reached their worst score since the inception of the GPI.

- 62% of those in extreme poverty are estimated to be living in countries at risk from high levels of violence by 2030.

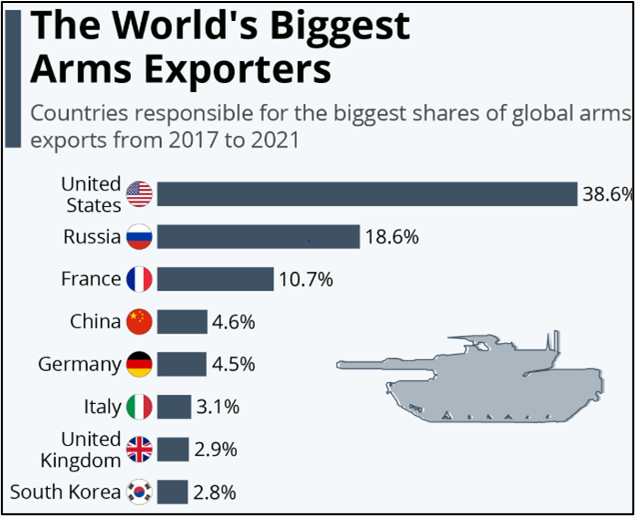

Another Question: Who is benefiting from war? Can this provide us with any answers?

We also explored questions such as, what is the human cost and how are we in Ireland/Europe complicit in war around the world? As Development Education practitioners we have to ask the question what, is the cost to ‘development’? ‘Development’ means wellbeing, lower inflation, more jobs, better education, health, housing, food security, economic, political and social stability. Research by the World Economic Forum (WEF) shows that as peace increases, money spent containing violence can instead by used on more productive activities. Conflict and violence cost the world more than $14 trillion a year, the equivalent of $5 a day for every person on the planet. According to the WEF just 2% reduction in conflict would free up as much money as the global aid budget.

The core question discussed by participants related to the future of Global Citizenship and Development Education (GCDE) in the context of war and peace. Some key points that emerged are the need for capacity building and resources for educators; the power of the personal story; deep dialogue; peace studies needed within GCDE; critical media analysis; asking questions; preventing war; taking collective action.

I would like to see learning groups within the wider GCDE community coming together around themes like war so that we can focus further on some of the issues raised. Through such working groups perhaps we can develop our collective knowledge, skills and methodologies, share resources, develop new resources and take collective action for to further support change.

Reflections from Zelalem Sibhat

At the beginning of 2018, the four sister parties making up the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the coalition governing Ethiopia at the time, investigated the drawbacks of the regime and concluded that they all bore responsibility for reforms where needed. Following this, Abiy Ahmed was selected as chairperson of the coalition and consequently prime minister of the state in March 2018.

At the beginning of 2018, the four sister parties making up the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the coalition governing Ethiopia at the time, investigated the drawbacks of the regime and concluded that they all bore responsibility for reforms where needed. Following this, Abiy Ahmed was selected as chairperson of the coalition and consequently prime minister of the state in March 2018.

Almost immediately, however, he started using what is known as ‘4D’ tactics (Defining, Defamation, Distinction, and Detaining) on Tigrayans, setting the course for genocide as follows:

- The government used documentaries and dehumanizing terms to defineTigrayans in various public speeches such as ‘Daytime hyena’, ‘Tigrigna speakers’, ‘Cancers’, ‘weeds’, ‘Greedy Junta’, ‘Looters’.

- The government and its allies worked to alienate Tigrayans form other ethnic groups. Other Ethiopians were conditioned to accept any punishment actions against the Tigrayans as legal and normal. In other words, Tigrayans were criminalised simply for being Tigrayan.

- While Tigrayans were illegally and unjustly detained since PM Abiy came to power this increased immeasurably after the onset of the war on Tigray in November 4, 2020. In October 2021, the state declared a state of emergency, which persecuted Tigrayans. Tens of thousands were detained and executed all over the country. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/06/crimes-against-humanity-and-ethnic-cleansing-ethiopias-western-tigray-zone

As educators, we need to engage and be a part of the answer to war and crimes such as those taking place in place in regions such as Tigray. Education, as a primary means of information in all societies, needs to take on board the fact that it can be an active force for peace and justice globally.

Reflections from Gerard McCann

In my discussion I reflected on three things related to the overall issue of how we engage with conflict as educators and indeed what it means for Development Education.

In my discussion I reflected on three things related to the overall issue of how we engage with conflict as educators and indeed what it means for Development Education.

The first was in relation to family experiences in Belfast during the conflict in the 1970s and how children’s lived experience was affected by that conflict. I drew on my own circumstances of growing up in West Belfast, looking at how our family and myself as a child were caught up in a war, how we coped and how the government at the time and subsequently never assisted in any meaningful manner in addressing the issues that the violence was having on normal families as victims of violence, witnesses to violence and as refugees. The point was also made that the education system in the North of Ireland has never adequately supported families which have been subject to the effects of conflict, the legacy of which continues to this day.

The second was based on my work with university colleagues in Lviv and Lutsk in Ukraine and with Ukrainian families in Poland during the war with Russia. I addressed the issues of family trauma, the refugee experience and how civil society and various supporting organizations responded to this crisis. I looked at the work of colleagues, some of whom were actively fighting in the war, and students who were spending their time trying to build their futures in the most horrendous of circumstances.

Finally, and as a last point, I commented on how Development Education and indeed education in general can respond to challenges brought forward by the exceptional circumstances of war. Arguably, Development Education has found conflict a difficult issue to work with. The complexities include having classes which may include students who have escaped conflict which teachers who maybe do not have the knowledge to navigate information pertinent to specific circumstances and conflict scenarios. Development Education has a role in providing information, training and providing positive outcomes for our understanding of conflict, peace building and conflict resolution. I concluded on this idea: Those of us who teach or learn about conflict, educate in a situation of conflict or work with those escaping conflict, need to consider our own position with respect to our role as humanitarian actors and peace-builders – in practice, we should be constructing a framework of hope and creating positive futures for all involved.